Book Chapter: What Is Self-Expression with Accountability?

© 2001 Michele Toomey, PhD

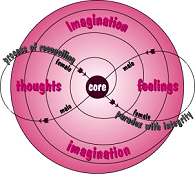

Self-expression with accountability describes a way of expressing with fairness and integrity how we think and feel, without being accusatory, judgmental, or abusive. Accountability is an honest claiming of what is going on for us underneath the words or actions that we are confronting. It is not a defensive reaction, a counter attack, a manipulation, a lie, a withdrawal, or a denial. For self-expression to have accountability, it must first have a confrontation, either of ourselves confronting ourselves, of another confronting us, or of us confronting another. Always, we must first confront ourselves to discover what's going on for us before we can be accountable and before we can confront another. I will illustrate how accountability takes discipline, courage, commitment, and brains.

Having said this, we need to note that in our communication system, when a message is received, the first thing that happens to us once the message is registered, is that we have a reaction to it. This reaction is spontaneous and automatic. Reactions have emotional feelings attached to them that have been shaped by our past experiences, our present experience, our anticipated experiences, and our degree of investment in the information. In other words, messages that trigger reactions go through our system with a "charge", positive, negative, or indifferent. This charge is not ours to edit or control. Reactions are to be registered as the first source of personal data relative to the information. They "inform" us and it is for us to discover what they are telling us. We must ask , "What is our relationship to this message and why is it triggering this reaction?" Therefore, right here at this initial stage, the integrity of our system can be violated if we do not confront ourselves to reflect on our reaction and its "charge".

Our first deliberate participation in the communication process, therefore, is reflecting on our reaction to a message. How we begin to deliberately participate in this process affects whether we are fair, respectful, and accountable to and for our reaction. If we are, we preserve the integrity of our system. Automatic reactions are joined by deliberate self-reflection to allow us to be true to ourselves. If we just allow ourselves to react to our reactions, which means staying in an automatic mode, we will have no rules of fair play and the integrity of our system will be violated. Reacting to reactions keeps us operating on the automatic response level. Reactions and reactions to them are not self-reflective. Accountability, on the other hand, is a deliberate, thoughtful claiming of what we discover is going on for us. To be accountable, we must be self-reflective and deliberate, and confront our reactions, thus the need for discipline. We must discipline ourselves to search inside and try to discover, understand, and claim what our reaction is telling us about what we're feeling and thinking. We must also claim what we've said and done and why, but we must never just react.

It takes discipline to be accountable. Reactions can be highly charged as they occur automatically, that is their nature. If not met with discipline their charge carries the energy and they just continue as chain reactions. They automatically trigger themselves and ask nothing of us. Even infants can react. Only the disciplined can be self-reflective and accountable. Teaching accountability means teaching discipline.

How does accountability takes courage? It takes courage to be accountable because we have to be honest and claim our part in whatever we said or did that we are being confronted about, either by ourselves or others. When confronted it is a natural tendency to want to duck the truth, either because we don't want to get in trouble, we are embarrassed and don't want to admit what we said or did, or we are angry at getting caught and feel trapped so we try to deflect, distract, defend or counterattack. Accountability leaves us unprotected, exposed, and having to deal truthfully with the effects and consequences of our actions. That takes courage. Hiding does not. However, we can be intimate only if we are accountable. Hiding may seem safer, but it is lonely and empty, say nothing of being a source of anxiety as we fear being exposed. Teaching accountability means teaching courage.

Accountability also takes commitment. Without commitment to fairness and integrity, we will never be accountable. We must " value" fairness if we are to" be" fair, and accountability is the fairest thing going. No one is ever in jeopardy when fairness is the governing principle. The same is true of integrity (honesty). If there is fairness, then honesty is not dangerous. It is, instead, a protection and a relief. Even though there will be consequences when we are accountable for what we've said or done, the integrity of the process will provide its own protection. The understanding and resolution that follow will bring an intimacy and a lessening of tension that provides a sense of peace and well-being, as well as a sense of being known and being connected. If we are committed to fairness and honesty, we can find the discipline and courage to be accountable. If we are accountable, the fairness and honesty bring us a sense of intimacy and connectedness, of personal stature and well-being. It is a powerful and rewarding process. Teaching accountability means teaching commitment to fairness.

Finally, accountability takes brains. Accountability takes brains because it is not just an automatic process. It is a deliberative and complex one. We need to be self reflective, ponder what is going on for us, search around in our past, present, and anticipated future experiences, and make the appropriate associations and selections of what is relevant to the particular confrontation. Then we need to draw on the discipline and courage it takes to express what we discover with fairness, honesty and accountability. This is a complicated thought process involving strong feelings that could easily just turn into automatic reactions. It takes no particular brain power to react and bully, or react and deny, or react and manipulate and lie. It is easy. Initially it is much easier than being accountable. The problem is after ... there is no relief, no peace, no understanding, no resolution ... just reactions. Accountability requires sophisticated thought processes, and is both emotionally and intellectually difficult. It takes brains. Hopefully, you can teach your students to learn to enjoy using their brain to be accountable and consider it as exciting as being shrewd, clever, or manipulative. Hopefully, their value system will prefer courage, commitment, discipline, integrity, and fairness, and the understanding and intimacy that follow. Teaching accountability means teaching complex thinking and processing.

Obviously, accountability is challenging, both as a process and as a process to be taught. You will be challenged on both levels, by being accountable yourself and by teaching your students to be accountable. So often we bow to the pressure of time and expediency, and just exact conformity. There are times when that is appropriate, but they are the exception, not the rule. Conformity may seem to be quicker and easier, but, in actuality, if it doesn't include some confrontation of the need for fairness and the students' acknowledgment that it's fair, conformity really buys us little. At best, perhaps a momentary reprieve. At worst, hostile acting out or silent smoldering resentment. Without a mutual agreement of fairness, conformity is the potential precursor of passivity, alienation, withdrawal, disinterest, depression, resentment or anger. Accountability is harder to have and harder to teach, but it always provides an opportunity for intimacy with the truth and with that comes understanding of ourselves and of each other, which in turn provide a sense of well-being. Trust is the wonderful byproduct of accountability. However, accountability is the outgrowth of confrontation, so we must also become skilled at confronting if we are to set the stage for accountability to occur.

What Is Confrontation?

A confrontation is an encounter that takes place on fair ground where each party equally has the right to be treated respectfully and fairly. It requires that both the confronter and the confronted address in an honest and straightforward way, what they were thinking and feeling when the exchange that triggered the confrontation took place. Addressing the issue that triggered the confrontation should lead to an honest claiming of what the involved parties' reactions were, and when done with integrity and fairness, this is accountability. For the confrontation to have integrity, the essential ingredient for fairness, the confronters must have the courage to reveal that they had a negative reaction to something that was said or done. Then they must reveal their initial reaction to the spoken words or actions that are being confronted. This expression of charged negative feelings takes discipline, because it must capture the negative charge in a fair and honest way, and not in a blaming way.

Just as with accountability, a confrontation exacts discipline and reflection, because it cannot be just an attack or a counter-attack. It must be preceded by a confrontation of one's self. Always the confronter must first be accountable before exacting accountability from the one being confronted. If the confronter doesn't reveal fairly and honestly why the confrontation is occurring, then the confrontation is already off to a bad start, even before the confronted one responds. Integrity and exposure are necessary ingredients for the ground to be fair and equal.

The relationship between confrontation and accountability is very circular. In order to confront with integrity and fairness, the confronters must first be accountable to themselves. So, accountability precedes a confrontation even as accountability follows from a confrontation, and confrontation precedes accountability, even as confrontation follows from accountability. In other words, we have to be willing to reveal what's going on for us even as we ask the confronted ones to reveal what's going on for them.

The complexity of confrontation with accountability is very real, and teaching it requires that you stretch yourself to deal with the complexity, both of the process and of your relationship to the process. You and your students have already learned ways to express yourselves when dealing with negative feelings such as hurt, anger, frustration, disappointment or fear. The majority of you will have grown up with some bad habits and some patterns that violate the integrity of the confrontation process. We often are used to hiding, explaining, defending, blaming or repeating the facts, but we are often not used to revealing the underlying feelings that are accompanying that explanation, that defense, that blame, or those facts. When dealing with fear, hurt, anger, frustration or disappointment there may also be some denial or manipulation of the facts and feelings underlying them. Possibly, attacking or ridiculing may also be part of that pattern. So, learning confrontation with accountability usually means unlearning some old ways of expressing ourselves that violate the integrity of our system and of ourselves, as well as learning some new ones that preserve its and our integrity.

Therefore, since how we express ourselves affects every interaction that occurs between ourselves and others, it is extremely important that we learn how to do it with integrity and fairness. Self-expression is so pervasive that it's more like the air we breathe than what we had for dinner. It is a continual, ongoing process that, unfortunately, is taken for granted. Since we, and our students, know how to talk, it is assumed that we know how to express with integrity who we are and what we need. That assumption is not only very wrong, it is very dangerous. We are very complex, paradoxical beings with a very sophisticated communication system. We must be taught the rules of integrity and fair play that govern this system so that we can participate in it without violating it.

Consider the following occasions:

1) A child, between 5 and 6 years old, experiences the death of a beloved parent or grandparent. The family grieves together but no one really talks directly to the child about the loss. Since the child is young, the family often assumes the child should be protected from the pain of grief, so the child is sheltered from and by the adults. This isolation and distance often leaves the child suffering in silence and alone. Years later, as an adult, the child may need therapy to help heal from the unresolved and unexpressed feelings. Or as an adult, there may be the pattern of silence whenever something painful occurs. The unspoken feelings may eat away at the spirit of the now adult who may fear intimacy because of the childhood experience of not dealing with the death of a loved one. It might also result in being caught in bouts of depression. Any number of negative scenarios could come out of this unfortunate sequence of silence. All of them avoidable, if only the painful feelings had been confronted with loving respect when they occurred, and intimate expressions of grief had been shared intimately with each other.

2) A middle school student is bullied but doesn't tell anyone. It continues throughout the year. The student is overpowered by the bully's intimidation and becomes withdrawn and sullen. The teachers notice the withdrawal and the lack of attention. As the student's grades fall, different teachers approach the student. Some teachers just give a lecture, some scold and warn of possible failure, some try to ask the student what's wrong. None of the approaches are successful. The student doesn't reveal what's happening or why the change in attitude, and even the teachers who try, don't press.

Eventually, if the student doesn't confront the feelings of fear and diminished sense of worth, the withdrawal and sullenness will become a way of life. If the teachers (or parents) don't confront the student more effectively, their acceptance of the change will become an accepted way of relating. All this began with the lack of confrontation of a bully. Now it has changed the student's attitude, self-image, sense of personal power, and mood, to the point that teachers are no longer relevant and learning is not the goal. For something to trigger a breakthrough, there must be an effective confrontation either of the student or the bully. Without accountability, the erosion of integrity is pervasive throughout the student's life, including and especially at school. Far better for the student if teachers are skilled in confrontation and accountability, then the possibility of an honest revealing by the student is greatly increased. Of course, even better, would be if the whole school was involved with teaching and exacting self-expression with accountability. Then the climate in the school itself would work against the power of the bully and the silent powerlessness of the bullied.

As you can see, the particular situations cited have universal themes. Each of them illustrate the need for treating information, both from ourselves and from others, respectfully. Our orientation toward it must be one of discovery not blame. Self-reflection and processing of information are designed to provide us with greater understanding, which, in turn, leads to intimacy not dominance or control. For our communication system to function in this way, however, its integrity must be maintained. There are principles governing the integrity of this system, and we must learn them and then abide by them. Confrontation and accountability are the vehicles for abiding by these governing principles. They preserve the integrity of our system.

In the example of a young child experiencing the death of a beloved parent or grandparent, there was a loss of integrity because discovery was not the goal, protection was. When the desire to protect precedes the desire to know, the path for intimacy and understanding is closed. A respectful and loving confrontation of the child's sense of loss and grief would have allowed the adults to discover how to be close to and with the child and how to let the child be close to and with its feelings. The child's participation in the rituals of memorial services would have been determined by its needs and desires. Instead, it experienced the loss and the grief alone and was left to go on with life alienated from itself, its feelings, and its family.

In the second example of the child being bullied, the child violated itself by not confronting the bully or its fears, its anger and its feeling of powerlessness. The significant adults in the child's life allowed this violation to continue and even when there were signs of something being very wrong, none of them demanded accountability from the child. Parents and teachers have an obligation to their children to confront them and to teach them self-expression with accountability. Again, the integrity of the communication system was not preserved because confrontation and accountability were not present.

When you were growing up,the way you learned to confront or not confront, and to be accountable or not , has greatly influenced your approach to confrontation and accountability that you have now, as well as your ability to role model and teach it. How you learn and grow from taking this course will largely be determined by the way you address your relationship to confrontation and accountability. This next section will be focussed on your experiences with self-expression and accountability, first when you were a child, and then as an adult. In order to discover what you must address within yourself if you are to be an effective teacher of accountability, you must first examine how your family, school, and, if relevant, your church or synagogue, dealt with confrontation and accountability. Within this context you will then need to reflect on how this past has influenced you as you consider teaching it. The most effective way to teach self-expression with accountability is to live it.

What Did You Learn As A Child About Confrontation and Accountability?

Think of your earliest memory of doing something wrong and being afraid of the consequences if you are discovered. I remember telling my first grade teacher that my mother wasn't home at lunch time and I had to get my own lunch. This was a lie that I'm sure I told to get the teacher's attention. I loved her and was always happy to have her care and concern directed my way. However, my mother discovered my lie and confronted me with it. When I "confessed", she told me that I needed to go to Miss Wysolmerski the next morning and tell her the truth, that my mother had not been home at noon, but she had left a sandwich and cookie for me. My dad was upstairs sleeping at the time because he worked nights, but, if I needed him he was there. I remember being chagrined but not afraid, and dutifully admitted my lie the next day when I got to school. I have no memory of Miss Wysolmerski's reaction or any negative feelings. In fact, this memory is a warm one for me. When I look at my report card for first grade, "Truthfulness" was a category on it, and I had "C" in truthfulness all year.

Obviously, this first lesson in accountability was done well, and I had the good fortune of experiencing accountability without fear or hostility. The pattern of white lies seems to have continued all year, but in some harmless mode that allowed me to grow out of it in my own time.

Activity

As you think back on your childhood, what is your earliest memory of being confronted and how was it handled? Write up a one page account of this experience and comment on its affect on you. Share it with each other in class and engage in a discussion on the various ways confrontation occurred and how the experiences were similar or different. Draw up a list of statements that characterize the positive experiences and contrast them with the negative ones. Conclude with a statement describing what elements a positive confrontation of a young child must have in order for it to teach accountability to that child in an effective way.

If my teacher had reacted angrily when I told her I had lied to her, if she had embarrassed me in front of my friends or if she had been harsh and punished me, my relationship to accountability and my memory of my first encounter with it would have been entirely different. Perhaps I might have stopped lying out of fear, or guilt or anger or shame. Instead of "C" in truthfulness all year I might have gotten an "A" and learned conformity, or silent alienation, but I would not have learned integrity. It took me a year of first grade to stop lying, but when I did, it was because I had developmentally arrived at the integrity in my own timing. I chose it, freely, without fear or guilt or anger or shame. I also felt free to be accountable when confronted again, because I wasn't mistreated or punished the first time. My mother and my first grade teacher taught me confrontation with accountability well, and to this day I not only remember that incident, I value accountability and the fairness it brings. I was very lucky. Not all children are as lucky. It is extremely important that you understand your own childhood experiences with confrontation and accountability and how they have affected your relationship to self-expression with accountability today. The following questionnaire will help us understand where you are relative to your ease and style of confrontation.

I. Relative to Your Family of Origin

1.) Ask your parents (or if they are no longer available, ask someone who might know, or answer what you can yourself) to share with you the following:

A) How did their parents confront? (Choose any that apply) Were they comfortable ___ fair ___firm___ or angry ___ attacking ___ blaming ___ or manipulative ___ withdrawn ___ resentful ___ other___

Please discuss their answers with them.

B) How were confrontations resolved?

fairly ___ with accountability __ appropriate consequences __ meanly ___ punitively ___ abusively ___ with conversations and sharing ___ with lectures ___ with arguments ___ in victory or defeat ___ never resolved ___ other _____

Please discuss these answers, also, and ask for examples.

C) What childhood memories do they have of being confronted by their parents? Of confronting their parents? Were they ever bullied by them, or by any siblings?

D) What was the practice in their schools, elementary through high school, and the church or synagogue, of confrontation and accountability? Were they ever bullied by teachers or other students? If so, how did they handle it? How was it resolved? Please give examples and reasons for their conclusions.

E) How do they think these experiences affected the way confrontation and accountability are practiced in your family now that they are the parents? How do they think they dealt with you (and your siblings if you have any) when they needed to confront them? (use the words from A and B questions) What is their response to bullying, physical or verbal? How do they think they have imitated their parents? How have they differed?

F) What is their view of fairness and a child's need for and right to fairness? Do they think they were fair with you? Do you think you were fair to them? Please explain.

G) What role did anger and fear play in their family of origin? What role do they play in your family with them as the parents?

H) Did they ever have a need for their parents to intervene at school for them? If yes, why and how did it go? If no, why not?

I) Did they ever confront the school for the way they were dealing with something regarding you? If yes, why and how did it go? If no, why not?

II. Relative to You

1.) How does your parents' history with confrontation and accountability give you insight into the way they have parented you in that regard?

2.) Are your memories and experiences with your parents consistent with their accounts of how they confront and exact accountability? Please explain.

3.) How would you describe (use the words from question 1, parts A and B) the way they confronted and the way you responded to them? What was difficult for you about their style? What did you like about it?

4.) What was the climate and the practice of accountability in your school and church or synagogue? What memories stand out for you regarding confrontations? How were they handled or not?

5.) How have these experiences influenced your ability to confront and be accountable? Where are anger, fear, fairness, and integrity for you today during occasions of confrontations?

6.) What has had a positive effect on you and what has had a negative one? Where are you regarding confrontation and accountability as you take this course? troubled ___ fearful ___ angry ___ apprehensive ___ used to reacting defensively ___ used to blaming ___ comfortable with my style ___ hesitant ___ unwilling ___ resistant ___ eager to learn ___ aware of ___ what I need to work on ___ other ______

7.) What skills do you think you need to work on? What strengths do you already have?

Discuss this questionnaire in small groups and begin to formulate a position on what you need from this course and what you bring to this course. Conclude this section with a 3-4 page paper on your history with and your current relationship to confrontation with accountability. Include your statement on what you want and need from this course and what you bring to it.

What It Takes To Teach Accountability

If we consider the many things you've discovered about your own evolutionary journey with self-expression and accountability, we can begin to draw some important conclusions about teaching it. Obviously, one conclusion is that the experiences you and your students have had with confrontation, fairness, accountability and integrity will affect the way you teach and the way they respond to your efforts to teach them self-expression with accountability. If you are going to be effective, therefore, you must take into consideration not only your past relationship to accountability, but theirs as well. To do that, you will need to deal honestly with yourself and your students, talking with them and to them. Real conversations and real connections will need to become part of your relationship with your students if you are to be effective in teaching accountability.

Another conclusion, then, is that you must become comfortable with talking with your students about themselves, not just about their courses. Teaching accountability will provide you with an opportunity to relate to your students on a more personal level. Alienation and isolation will be more evident to you and the intimate connection between students or between teachers and students, when self-expression with accountability is implemented in a school, tends to reduce and even eliminate alienation. No one is expected to become a "therapist", rather, you will be expected to be a true educator, educating the whole child. Teaching students how to express themselves as in integral part of their education means that as their teacher, you must be able to express yourself as well. In this age of "merit" ratings and the emphasis on state and national testing of subject matter, the measure of a good teacher and a good school could get reduced to a content test score. Teaching self-expression with accountability asks teachers to value the whole child, and evaluate true education in a broader and deeper way than just knowledge of subjects. It asks you to measure how they are relating to themselves, each other, and to you, as well as to learning and achievement.

Of course, knowledge of subjects is important, but if it is the only valued knowledge, a student's ability to process personal information and express it with integrity and accountability will be ignored. We are in the midst of an era marked by hostility, alienation and violence. This is hardly the time to ignore what students think and feel. This is the time to care about them as we teach them to express themselves and process what they discover. Intimacy and being known and understood is a critical need for them. They cannot be eager to learn and achieve if they are feeling alienated and depressed.

Let's look first at your profile of where you are regarding confrontation and accountability. I will try to address your various needs. If you are: Apprehensive, hesitant, and fearful: You will need to remind yourself of what you learned about your family history and how it has affected your comfort level and skill with confrontation and accountability. If you are apprehensive and fearful, you will tend to withdraw from a confrontation and be defensive or protective when confronted. Accountability will be hard for you because it will give you a feeling of vulnerability.

Your disclosure to students as you introduce them to self-expression with accountability, will need to include some anecdotal information that reveals your hesitancy and apprehension. Some students will have similar experiences and you can ask them to share them. Other students may have different experiences they want to share at this time. The process of doing "equal" and "intimate" will have begun.

The discussion can then turn to fairness, and the protection it provides for everyone. You and they can again share stories of times where things were handled fairly and when they weren't. Then, you can assure them, and yourself, that self-expression with accountability demands fairness and is fair. Everyone is safe when fairness is the reference point. This would lead into a discussion of the fact that confronting calls for an honest claiming of what one said or did and why. The purpose of the confrontation can be explored as a way to discover and understand. Discovery to better understand is not the same as a witch hunt in order to blame. Understanding leads to knowing and then accountability leads to caring and respect. This system isn't harmful to anyone. Rather, it prevents harm.

As time passes, and you and your students begin to confront and be confronted, and accountability begins to occur, you will all need to claim and attend to your fear as it crops up and needs attention. If dealt with respectfully and fairly, the fear will be calmed by the fairness and care. Left unattended, fear can skew the process and prevent honest claiming. This would be detrimental to the integrity of the process and prevent real intimacy and accountability. It's not that you and they can't be afraid, only that you can't pretend. The fear will be reduced and often eliminated as you teach and learn how to treat respectfully and fairly everything that is shared and claimed.

Angry, Defensive and Blaming: Again, you will need to put your anger in historical context with your past. Find some anecdotal way to claim with your students that you will be working on not reacting angrily or defensively or resorting to blame when the need for a confrontation occurs. Again, solicit experiences they have had with hiding behind anger and defensiveness and being blamed or blaming others. The feeling that you are all in this together trying to deal with the heat of anger will free you and the students up to dare claim those feelings when they get triggered.

Further discussion needs to occur, however, on the strength of the pattern of reacting angrily and attacking or defending. The force of anger is often an out of control force that is so ingrained it takes great discipline, commitment and continued practice to change it. The following paper is appropriate for this discussion. Please read it and then discuss it together, both as it relates to you learning to express yourself fairly and for teaching it to students.

"Learning How to Be True to Our Emotions without Being Abusive with Them"

As complex paradoxical beings, we have the capacity to experience many emotions, and often contradictory ones at the same time. We can be excited and eager even as we are afraid and cautious. We can feel relieved even as we are worried. And we can feel anger and disappointment even as we feel regret and understanding. The range of emotions we can feel is both a wonderful gift and an awesome responsibility, since every emotion has the potential to free us to be intimate with ourselves or others, even as it has the potential to be used to violate. There is a way to deal with emotions that is honest, fair, respectful and caring, and therefore, liberating and intimate. Yet, there is also a way of using emotions abusively that is violating and oppressive. I would like to discuss with you what we need to know and do if we are to be emotionally liberated, not emotionally oppressed and oppressive.

First, let us explore what it means to deal honestly with our emotions. Honesty requires that we take the time to register and then recognize that we are feeling something, and then seek to discover what it is we are feeling, where it is coming from, and why this feeling or these feelings have been triggered. To be honest we cannot deny, deceive, diminish or exaggerate our feelings. We must claim them and then try to understand them. An honest search of ourselves, of what associations and images come to mind, and what reactions we're having, will allow us to discover as much as we can about what is going on for us. Then, as a journeyer, we must process, not judge, what we discover, trying to understand what it all means and where it's coming from, so that we can be known to ourselves.

An honest attitude and an honest approach to ourselves frees us to discover the truth about ourselves to the extent we are capable at the time. Knowing the truth about how and what we feel and why allows us to know ourselves, and knowing ourselves is what will free us to be true to and intimate with ourselves. It is this integrity, this honesty and this intimacy that frees us to journey through life known to, not alienated from ourselves. Then when we attempt to communicate with others, we are able to begin with an honest claiming of what is going on for us. Any interaction with others that is based on such an honest expression of what we are experiencing has the potential for intimacy and a respectful exchange with another.

It is not as simple as it sounds, however, to be honest about how we feel, and that leads to fairness, the next issue needed for a liberated intimate relationship with ourselves and others. There are many unfair biases that interfere with honesty about how we feel. Sexism and racism are two major biases. Sexism unfairly attributes weakness to females and labels emotions that are seen as signs of weakness suitable only for girls and women. It ridicules boys and men if they display any of what is considered the weak female emotions such as fear or anxiety, sadness or upset that is expressed with crying, gentleness and caring that is expressed tenderly, or feelings of loneliness, dependency and need. Sexist bias defines masculine as strong, aggressive and independent. The one emotion that boys and men can express to prove their strength and masculinity is anger. Anger is expected to carry a male's emotional life without jeopardizing his image as strong and masculine. Anger, therefore, is over-used by boys and men and under-used by girls and women who are influenced by these sexist assumptions.

The unfairness of considering any emotion as a sign of weakness or strength violates the integrity of the self, which has the need and the capacity to experience every emotion and for whom every emotion is legitimate. To be emotionally honest in the face of sexism is not easy, and it is certainly not easy for adolescents who are in the midst of establishing their sexual identity. In a society where strength is considered superior to weakness, and males superior to females, it is not surprising that adolescent males rely heavily on anger to prove their masculinity and adolescent females who resort to anger to show their strength run the risk of jeopardizing their femininity. To be emotionally honest with vulnerability of any kind is to confront the image of weakness and face it down as a lie. This kind of honesty is not easy; in fact, it is extremely difficult. Yet, honesty is what is needed.

Anger has its rightful place in our life, but it has no right to dominate it. In fact, any emotion that dominates us, violates us. We should never be dominated by any emotion. As paradoxical beings we must move back and forth between our contradictory feelings and never be overcome by only one. Neither our feelings of vulnerability nor our feelings of strength should dominate us. If they do, we lose our freedom to move and to choose. Feelings of vulnerability must be matched by feelings of strength, and vice versa, or fear and anger will dictate our life choices. If we become only aware of our vulnerability we will be always fearful and afraid to risk. Once this occurs, anxiety accompanies any decision and we become prisoners of our fear. Dominated by the need to feel safe, we lose our ability to venture and our world gradually becomes smaller and smaller and so do we. Eventually we become a caricature of who we are and an exaggeration of what we fear. We lose the integrity of our paradoxical complexity and as that occurs we lose our freedom. We may even lose our voice, since fear often keeps us silent.

On the other hand, if we choose to deny our vulnerability and only focus on feeling strong, we will become another caricature and an exaggeration of ourself. We will hide our vulnerable feelings beneath the intimidating expressions of anger. If we get upset, we react with anger. If we are disappointed, we get angry. If we are lonely or depressed, we are angry. If we feel hurt or rejected, we lash out with anger. Everywhere and every time our response to an emotional situation is anger. We are loud in anger. It drowns out other feelings and drives them and others away. Dominated by anger, we become alienated from every other feeling hidden underneath it and we prevent both ourselves and others from getting close to us. We become known only from our anger. Because it is loud and aggressive, anger appears to make our world bigger when it dominates our emotions. Actually, it serves only to reduce it and our world is as confined by anger as it is by fear.

Any emotion that becomes our primary and possibly our sole emotional expression, limits our capacity and violates our complexity. Anger, when allowed to get out of control, violates others as well. It has the force to intimidate and the fear it invokes has the added dimension of possible physical violence. Anger, therefore has the potential to be both emotionally and physically abusive and therefore is doubly to be feared.

Yet, these two emotions, fear and anger, keep sexism and racism alive. Whatever racist assumptions are made about any particular race also feed on fear and anger and a false sense of superiority or inferiority. Gender and race are both birth rights, and biased assumptions based on them violate the person with the bias and the person who is the object of it. In racism, the race that conquers and dominates another is considered the superior race, as is the race with the greatest anger. Righteous anger is a racist way of claiming superiority. Often, gentler nations and races are looked down on as too much like women, and female weakness is attributed to them because gentleness is seen as weak.

We are left to deplore sexism and racism and the violation it does to our integrity and our complexity. Honesty and fairness are jeopardized, as we have seen, but so are caring and respect. If emotions are to be treated respectfully and caringly, we must not have disdain for any of them. To be true to our emotions without being abusive with them requires us to treat each and every emotion we have with the greatest care and respect. Just as honesty and fairness go together, so do care and respect. When the gentle tenderness of caring is coupled with the attentive firmness of respect, our paradoxical nature is at one with itself. Respect without caring becomes too stiff and formal, while caring without respect becomes too soft and indulgent. Together, caring and respect bring attentiveness and warmth. Our feelings must be both attentively cared for and respectfully addressed.

What does this actually mean? If we become afraid, we need to put our emotional arm around ourselves and in a caring way, ask ourselves why we feel afraid. If our fear is not honest and fair, it can spin out into hysterical out of control anxiety, and our hold on ourselves must be very firm to exact accountability before we give care and concern. Whatever honest and fair answer we give ourselves after that, we would then need to say how sorry we are that this fear has been triggered and then ask ourselves what we know about why it got triggered and what we need in order to calm it. Then we need to ask if there is anything we want done about it. If the answer is yes, we need to ask what and why. If the answer is no, we need to ask why. In either case, our questions and responses should be non-threatening and invitational even as they are direct and accountable. If what we say is honest and fair, and what we need is respectfully listened to and cared for, we will have responded with the integrity and fairness, care and respect that frees us to be true to our feelings, and not abusive with them.

If we become angry, we would need to firmly put our arm around ourselves so that we can contain the strength of our reaction until we check to see if it is honest and fair. If our anger is honest and fair then we have the space to explore why we are angry and to be respectful and caring of our angry feelings. If our anger is not honest and fair, then we must firmly hold ourselves in check until we discover what emotion is underneath the anger. This is a critical time for any emotion, since indulging an emotion when it is not honest and fair violates our integrity and this throws our system of checks and balances off and it and we become out of control. With anger, that means we may act violently toward ourselves or toward another. Attention to the honesty and fairness of anger is our greatest protection against being abusive with it. Honest, fair anger can be expressed as ours and explored as to why, without lashing out at others and abusing them just because we are angry.

Unfortunately, anger is often used abusively, and we may have learned to react abusively without giving it a second thought. This means we are caught in a pattern that is out of control and therefore we are out of control. Anger is not the only emotion that can lead to being out of control, any emotion can, and the self-indulgence that results from this pattern is destructive. We lose our freedom and our integrity when we are out of control. There is no justification for being out of control even though there may be very understandable reasons for why and how we became so self-indulgent. Our hope lies not in out of control reactions, which only violate and imprison us, but in gaining control of our responses to our reactions, so that we can be free to be true to them, not abused by them.

Expressions of honest, fair anger need to be statements of why we are angry and how it makes us feel. They should not be abusive clubs and dangerous weapons meant to destroy ourselves or another. Destruction and conquest are violent acts and are not respectful or caring to either ourselves or others. They make us into vengeful marauders and self-indulgent bullies who leave devastation in our wake. What we need to be aspiring to is anger that frees us to be true to our strong feelings of unfairness, not anger that violates with its own abusive unfairness. No emotion should be so indulged that it dominates us and spins us out of control.

Every emotion should have its rightful place and its turn, as the occasion arises that calls it forth. And when it takes its turn and we express how we feel, we should be fuller in stature and freer in expression and truer to ourselves than we were before we spoke. If we are an exaggerated caricature of ourselves, out of control and alienated from ourselves, something is terribly wrong. Our liberation is dependent on a complex relationship with ourselves. We must be self-disciplined, even as we are self-indulgent. We must be free to express ourselves even as we are self-contained. We must reflect as well as react. We must be honest, fair, respectful and caring with every emotion we feel.

And we must never endorse abuse and violation either of ourselves or of another. We must, therefore, learn to process our emotions, not be at their mercy, if we are to be true to them and to ourselves.

You are, therefore, trying to teach and model, expressing anger honestly but not abusively. It is never that we must not have our anger. Anger, like every emotion, is ours to feel and attend to when we have it. But anger is not a license to club ourselves or another person verbally. In self-expression with accountability, you are being asked to teach students how to express themselves, how they are feeling when they are angry, and why they are angry. Their anger should be listened to, responded to, and respectfully dealt with, in a fair way.

The more they understand that anger will be respected and dealt with fairly, the less they will get caught in defensiveness or blaming. Whenever blame gets going, it shifts attention away from the reasons for the anger to the one who triggered the anger. Not only is it abusive to rely on blame, it serves no purpose for discovering why the person acted or said what they did. Instead of a discovery process, there is a battle, where sides are taken and defending and attacking characterize a hostile exchange. Fairness is not the point, winning is, so the better the attack the better the chance of defeating the enemy.

We are, therefore, relying on fairness to provide the protection for everyone. The more you can demonstrate how fairness works, the more your students can grow to trust it and you. The more trust grows, the less hostility and alienation are felt. Trust invites connection and a sense of belonging. These feelings create the climate for a rich learning environment.

The capacity to learn and be attentive, even eager to learn, is heightened by the security of education in a communications context where fairness and trust are the norm. Self-expression with accountability creates just such a climate and educational opportunity.

Perhaps some examples of confrontations with accountability would be helpful.

Grades 1 - 3: A little girl in your class, we'll call her Katrina, is crying and when you ask her what's the matter, she tells you another little girl, we'll call Jane, is having a birthday party, and she's inviting all the girls but her. You make an occasion to talk with both little girls together, asking Jane why she told Katrina she was the only one not invited to her party. You explain that she has a right to invite anyone she wants, but that it's mean to make the one who's not invited feel bad because she's excluded.

You try to discover what's going on between the two girls. Maybe they had a fight, maybe the uninvited Katrina is unliked. Whatever the situation, you're trying to find the fair resolution. If there's been a fight, you should be able to help them resolve it, claim how they feel and why, then be accountable for their part and apologize where appropriate and make up.

It might go something like this:

Teacher: Tell me what happened?

Jane: "I was talking to Denese and Katrina came over and shoved me. I fell down and it hurt. I'm mad at her and I don't want her at my party."

Teacher: "Why didn't you tell her that?"

Jane: I don't know. I didn't want to be nice to her."

Teacher: "Do you realize that was as mean as Katrina shoving you?" "Why did you shove Jane, Katrina?"

Katrina: "I don't know."

Teacher: "Oh, I bet you do. Were you upset that she was talking to Denese?"

Katrina: "Maybe."

Teacher: "Why?"

Katrina: "She always talks to Denese and never talks to me. She was my best friend. It hurts my feelings."

Teacher: "Why didn't you say that? It's not fair to shove her instead of using words to tell her why you're upset. Why did you shove instead of talk to her?"

Katrina: "I don't know. I guess I was just trying to hurt her like she hurt me."

Teacher: "I'd say you two really need to talk. Jane, did you know you were not paying attention to Katrina? Had she upset you?"

As you can see, there's a way of trying to discover what's underneath the incident of the party that eventually will allow you to get to a place where each girl better understands what happened and then they can apologize to each other and usually it's very natural that they make up. Each feels better having been heard and hearing the other. In all probability, Jane will now feel free to invite Katrina to her party. If she doesn't, then it's a hard lesson for Katrina, but it has been dealt with fairly, so she will, in all probability, realize that words are better to use to resolve something than shoving or any physical violence. In time, Jane will probably get back to being friends with Katrina, but if she doesn't, each girl will have begun to learn that friendship needs sharing and talking if it's going to thrive.

Grades 4 - 6: You are in the cafeteria and you observe a group of boys shouting at each other and before you get to them, they are pushing and hitting each other. When you get to them they can't seem to stop and it is getting out of control. You speak loudly and firmly to them and tell them to step back and stop all talking. You send them to the office and follow them in, as you walk with them. In front of the principal, if possible, confront them on their behavior and ask each boy to tell what was going on for him.

Again, you are trying to diffuse the situation by listening and asking each one to express himself with respect and fairness, not attacking or blaming the others, just claiming what was going on for them that triggered the fight. Going to the principal's office helps to lend seriousness to your intervention and to the incident.

As each boy expresses himself, the unfair events will unfold. You will be trying to teach them to express what's happening to them, not just react and then act out. Remind them it takes discipline and brains to use words in a fair but confrontive way, while reacting and acting violently takes neither.

Regardless of the particular circumstances, there is generally some feeling of being mistreated and being justified in getting physical. Your task is to discover the nature of the mistreatment and then get the boys to use words to express it. When they confront the offender(s) it should be respectful and fair, so that you can expect an honest claiming from them. They need to reveal why they acted the way they did, and when they do, the affronted boys should better understand what happened. Often, this allows them to cool down and feel connected because they have been in that spot before and not handled it well.

As the claiming continues, unless it's a very hot issue, it should begin to cool, and students are better able to express themselves and be better understood. Some consequences may have to be meted out, but they should be fair and reasonable so that being accountable has credibility and yet is not seen as merely punitive.

Do not allow attacks or blaming. Do not get angry or blaming, either.

The tone would be something like this:

Teacher: "I do not want to see fighting in the cafeteria again. You can get angry and upset, but you are expected to use words to express those feelings and demand accountability from each other. Now, how did this get off on the wrong track?"

Student A: "That stupid jerk Joe ..."

Teacher: "Wait a minute. Name calling is one of the best ways to trigger a fight. Rephrase and start over. Why are you upset with Joe?"

Student A: "We were trying to tell Joe that he played dirty at gym, and just because he got away with it we weren't going to take it."

Teacher: "Joe, what do you have to say for yourself?"

Joe: "I didn't do anything. Those babies just like to whine..."

Teacher: "Wait. Again, no name calling. What did you actually do?"

At this point, Joe may or may not claim his foul play, but other students who were playing with him need to say what they saw. They may feel it wasn't that bad or that he was really out of line. You are trying to hear and let them hear, the different way his actions were seen and evaluated. The particular boy he fouled needs to say how it was for him. Joe needs to hear and be heard.

Eventually, you will feel you understand what happened, and you need to have each student be accountable for whatever they said or did that either aggravated the situation in the cafeteria or helped it. The learning that should take place should involve how to handle it in gym class and not leave it unaddressed and then fuel a fight later. They need to be reminded that they should have worked it out with the gym teacher. Before the next gym class, the gym teacher should be informed of what happened and the principal or the teacher should be present while the boys tell the gym teacher what they should have told him at the time. Appropriate steps should be taken to take care of the initial "foul play", accountability should be there on everyone's part, including the gym teacher, and the process of confronting at the time should be reinforced.

In addition, the fracas in the cafeteria needs to be looked at and re-phrased so that the students learn how to express strong feelings and be heard and responded to and accountable before a fight erupts. As this procedure becomes the norm, students learn how to express hot anger without attacking and how to be accountable without feeling defeated. They end up feeling proud of themselves and beginning to appreciate the power of words.

You, on the other hand, must be willing to take the time to deal with the situation in a way that invites sharing and claiming. It takes longer than just correcting and scolding or punishing immediately, but in the end it saves time because students learn to express themselves and confront and be accountable. The feeling of relief, and safety that comes from the trust that fairness creates is more than worth it. Your students learn to operate on a more sophisticated and complex level that gives them a sense of pride and stature. They feel powerful with the integrity of a powerful process that yields fairness and accountability. You and they will become proud of what they say and do when handling anger, fear, hurt, embarrassment, or disappointment. The aura in your classroom and school will be clear and comfortable, safe and respectful. A sense of community will evolve and true education will have its best shot. More than worth the effort and commitment teaching self-expression with accountability exacts.

Finally, an example of a confrontation with adolescents:

Grades 7 - 12: Some of your girls (we'll call them Rita, Ann, Ella) come to you and tell you the boys are forming a gauntlet in the corridor and grope and grab and taunt the girls as they walk down the corridor. They don't want to give you names.

Teacher: "I know you are telling me because you want me to stop this abusive, sexist behavior, and I certainly will, but to do that, I need you to help me. I need you to dare tell me who the boys are.

Rita: "They'll get mad at us and call us squealers. Can't you just catch them doing it?"

Teacher: "I might be able to catch them, but I am not even on that floor. What are the chances I could catch them? Besides, you need to find the courage to confront these bullies."

Ann: "Easy for you to say. You know how those guys are when they get going. We'll never have any peace and it's intimidating!"

Ella: "Yeh. I'm scared of them."

Teacher: "I understand. However, as a school, our job is to provide you with a safe environment. It's our obligation to stop this behavior, even if it means suspending or expelling those boys. That abuse can't be tolerated. The only way to change it is to confront it and the only way to learn how to stand up for yourself is to join me as we stand up together against these bullies. Let's start by going to the principal and telling him what's occurring."

Ella: "I want you to take care of it. I don't want them to know we told on them."

Rita: "Me, either."

Teacher: "You trusted me or you wouldn't have come to me." Now, I'm telling you, we need to do this together."

With the principal's help, the girls give the names of the boys (George, Al, John, Tony, Mark) and they are called into the office to be confronted.

Principal: "You boys need to hear what Rita, Ella and Ann want to tell you."

Ann: "You have been physically assaulting us, groping us as we walk down the hall. It's humiliating and it scares us. We hate it and you have no right.

Al: "Oh, come on, we were just kidding. Don't be such a baby."

Teacher: "Stop pretending this is a game. The only ones having fun were you boys. You were sexually assaulting the girls. That is a crime, not a game. If you don't want us to call the police and press charges against you, start being accountable for what you did."

George: "We were just having fun. We didn't know they didn't like it. We don't want to be arrested.

Teacher: "We all realize you were having fun, but you were doing it by abusing the girls. It was obvious to you they weren't having fun. How did this whole thing get started? Please start talking honestly and being accountable. This is about claiming what you did and why, and then understanding what it cost the girls. The point is to re-establish fairness and respect and stop the abuse. So, how did this get started and why?

Tony: "Well, we saw a video where the naval officers were drinking and then went out in the hotel hallway and grabbed at the women as they passed by. Looked like fun to us. Then when we tried it, it just got to be a regular way to feel like one of the group."

Rita: "Why didn't you even care that we were so upset and couldn't stop you. You treated us like sex objects. I thought we were friends."

Tony: "We are. I didn't think of your feelings. I just thought of myself and my guy friends. Sorry." Once one boy says he is sorry, the accountability should begin. It breaks the argumentative, defensive tone. Now you're trying to explore, one at a time, what each boy was thinking when he participated in the taunting and physical groping. Each should apologize, and the girls should each express what it was like being the targets of the abuse. The principal should administer some appropriate consequence for the behavior with the admonition that if it occurs again, there would be suspensions.

If things go well, everyone is feeling treated fairly, there is a better understanding on the boys' part of what it was like for the girls, and a better understanding of what was going on for the boys. The behavior should stop, but if it doesn't, the suspensions should occur. There must be follow-up if the students are to trust the accountability process.

In conclusion, to teach confrontation with accountability, you will need to commit yourself to the protection of being fair and teaching fairness. That means you and your students will be on a journey of revealing when you and they feel you and they feel you are being treated unfairly. You will also need to be committed to not tolerating unfairness. This journey requires the discipline it takes to discover why unfairness is being felt and how to stop it. Out of this discovery process should come a level of understanding and respect that allows for movement and a re-establishment of fair play. Students will learn how to express themselves without being abusive, and how to resolve unfairness without hostility or vengeance. Through confrontation and accountability fairness is able to be maintained, and fairness is the source of safety, and that yields a sense of well-being. This in turn allows the focus of teachers and students to be on education and not on a preoccupation with feelings of alienation, fear, or anger.

Activity

Write the dialogue to finish each of the examples of a confrontation, and in class, role play each of the scenarios as you have concluded and resolved them. Discuss and evaluate them relative to whether they are fair and accountable. Choose those scenarios that you think are the better examples of a confrontation with accountability. Discuss what influenced your decisions and what distinguished those particular scenarios. Write a paragraph on what you learned from the exercise.

|