Book Chapter: Capturing the Positive Force of Fairness to Prevent the Negative Force of Violence

© 2000 Michele Toomey, PhD

Fairness may sound like a simple concept. Webster defines it as "marked by impartiality and honesty". However, any real pondering of fairness opens up a complexity of considerations. Does impartial mean objective and without passion? Are bias and prejudice automatically part of subjective strong feelings and beliefs? How do we know what's fair and who's to say what's fair? And what's more, how can fairness be a force in the face of self-indulgence, greed, hostility, anger, violence or revenge?

A thoughtful exploration of fairness is certainly where we need to start if we are expecting to prevent hostility and violence by teaching accountability and fairness. We are forever encountering situations that we feel "aren't fair". People even write books about the unfairness of life or get angry at God's unfairness because bad things happen to good people. At least here in America, where our country was founded on the belief that we all have the inalienable right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, we philosophically endorse fairness. Living out of that philosophy is another thing, but as a nation we embrace it in principle. However, does that make us a nation of fairness?

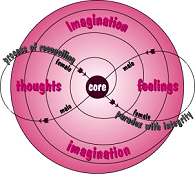

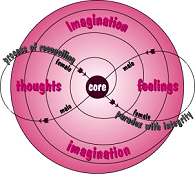

Why is fairness so difficult to live out of and apply? Primarily because it goes to the core of one of life's essential dilemmas, the relationship between our own paradoxical (contradictory) needs and desires. We both need and want fairness even as we don't want it. We know we need to find a fair balance between self-indulgence and abstinence, but striking that balance is complicated by the strong draw toward indulgence. We are capable of thinking and feeling, but we are taught that thinking is superior to feelings and that feelings can be dangerous, so thoughts need to control them. Fairness is hard to establish within ourselves when we are conflicted and when one dimension of ourselves feared and the other dimension is expected to control it. Is this conflict fair to either dimension? To us? Doesn't it set us up to be at war with ourselves?

Are you beginning to get the feeling of the complexity of our relationship to fairness? Add to this, the paradoxical relationship of ourselves to others. We both want to be connected to others and we want our own space. We reach out and we slap away. We want to share and we want it all. We are drawn to others and we fear others. We say all are created equal and then our prejudices enter the scene. We don't want to be inferior so we decide we're superior? Is that fair? Now we need to prove our worth? Life becomes a test instead of a journey. Is that fair?

A bit overwhelming, you may say. Perhaps impossible to sort out in a way that we can live in fairness, you may fear. Too idealistic to actually achieve, you may decide. Understandably, fairness can be an illusive quality that seems to elude us. However, fairness is something so essential to our system that with the right orientation we can not only live out of it, we can know fairness and feel safe and at one with ourselves in it. This security and intimacy with ourselves on such a deep level fulfills a fundamental need for us. It also allows us to find inner peace, that by nature we long for and have the capacity to treasure.

The power of fairness, therefore, lies in its integrity (its honesty) and in ours. As complicated as fairness is, as many factors as it entails, and as much as it demands, fairness is intrinsically known by us because it resonates with our natural integrity. It is, then, not only possible for us to live out of fairness, it is our mandate. Without fairness, our integrity is violated and we cannot be whole and at one. So, knowing fairness itself, is not what you are being asked to teach, rather, teaching how to be fair and how to participate in this very complicated process of living in, with, and out of fairness is your mandate. This process and the vehicles that maintain fairness within our system have to be learned. They are complicated and are not just automatically known.

Just as the need to communicate is essential, and the capacity for language is naturally available to us, we must still be taught how to communicate with language. Unfortunately, we cannot learn how to live out of fairness as easily as we learn how to communicate through speech, because the speech we learn is often unfair. It is frequently designed to protect, dominate, defend, attack, lie, manipulate or deceive. Fear is a predominant factor in the patterns of speech and the power of language. Fear of being dominated, attacked, caught, punished, or discovered as being vulnerable, complicates our relationship to fairness. To dare live out of fairness we must feel safe enough and trusting enough to reveal the truth about ourselves.

If a school community wants its members, both faculty and students, to relate to each other respectfully and fairly, then it must provide a safe environment. This does not mean just physically safe, but also psychologically safe. If fears are to be overcome and trust established, the climate of the school and the guiding principles for interacting with each other must be respectful and fair. Bullying can't be allowed to go unaddressed. Verbal and physical abuse must be dealt with fairly. Students must know that what is being asked of them is being asked of everyone and being exacted of everyone. Ideally, then, your whole school will be engaged in learning how to confront, be accountable and relate with fairness and respect. However, if you become a teacher in a school that isn't formally on that path but philosophically endorses it, you can begin with your own students and offer them the opportunity to learn it. If your school does not endorse accountability and fairness, beware of the climate there and its potential for abuse and violence. Ask yourself if you want to teach in such a school.

What is Fair and How Do We Know What's Fair?

As we have noted, fairness is impartial and honest. If we go back to some of the initial questions this definition triggered, it is important to look at impartiality. So often, we miss the key elements of impartiality, and hide behind "objectivity" as the criterion for fairness. That, then, makes intensity of feelings and passion, suspect. We seem to carelessly assume that cold, calculated reasoning that speaks in terms of distance and being "objective" will automatically result in fairness. Ironically, it's not the intimacy or the passion that interferes with fairness, it's bias and prejudice that's the issue. If ever we needed a clear example of that, we need only look at the legal profession. Judges are guided by legal precedent and laws. They are supposed to "objectively" and "judicially" apply the law. It is certainly cold, factual and distant. Yet, their interpretation and sentencing decisions can reflect their biased views and prejudices. Some judges blame women for being assaulted or raped, because they wore provocative clothing. Sentencing of the violator or rapist can be much less than one would expect because of the judges sexist bias.

The fact that we feel strongly about something, does not have to prevent us from being fair about how it should be resolved. In all the years I have dealt with children and adults, I have never found that they can't understand what's fair. Whether they have the integrity or the commitment or the discipline to " be" fair is something else, but knowing when something is fair is not usually the issue.

I have had 5 year olds tell me, "I know it's not fair when I hit my sister, but she's not fair when she breaks my toys". Or, when in a family session with a 5 year old girl who has a teasing, taunting father, we are discussing the fighting and tantrums that occur when they both want the couch, and she suggests, "Why don't we take turns and each one have it every other day? Wouldn't that be fair?" She understood fairness even if she wasn't always able to live out of it.

Then there are adolescents who struggle to be tolerant of each other but tend to be sarcastic and ridiculing, which at times can erupt into physical violence. Once, in a boarding school setting, an Asian boy was being bullied by some of the other boys because he was always cooking his native foods and "smelling up" the dorm and his room. When the boys were brought together to confront each other, the Asian boy confronted the meanness and abuse directed at him. The other boys responded by saying the smells were strong and stayed in the dorm for hours and it bothered them. What followed was profoundly touching. The Asian boy spoke of his lonesomeness for his country and his parents and how the native food made him feel less lonely and more connected with his home and his own nationality. Once that door was opened, the other boys began to soften. They said they were sorry for being so selfish, and that they could understand how important the food had become. In the end, they worked out times when cooking would occur and times when it wouldn't. Everyone shook hands and that was the end of that hostile controversy.

When our orientation is integrity (honesty) and fairness, and we demonstrate that we expect things to be resolved with integrity and fairly, there is an opportunity to go to what's underneath the issue causing the problem, and begin to understand better what the involved parties are thinking and feeling. This greater understanding leads to being better known, to intimacy, and this intimacy of being better understood and better known leads to better relationships. Instead of being stuck in reactionary fighting, the intimacy and knowledge allow us to move toward respectful caring and understanding. That's the power of fairness.

The only time strong feelings get in the way of fairness is when fairness is not the goal. For example, if you listen to many of the talk show programs on television and radio, they argue their point, put the other person and their point down, never see the other side, and only want to win the argument. Fairness is the farthest thing from their minds. In the case of people who are invested in getting their own way and what they want no matter what, they do not have fairness as a goal, and it has no power with them. Often, divorces are bitter and hostile and one or the other or both of the partners feel victimized by the other. In those cases, fairness is not the goal, getting back at the other is the driving force. If they don't resolve their hurt and angry feelings over the divorce, fairness doesn't have any attraction or power in arriving at their settlement. Some states try to enforce fairness by having everything divided in half, but, even the law can't mandate fairness effectively if the parties involved are invested in winning or destroying the other.

Of course, whenever enemies are declared and war is waged, either psychological or physical warfare, fairness has no power. Enemies don't want fairness, they want victory and revenge. Needless to say, enemies are the last thing we want in a school community, and war is the last thing we want waged. Creating a climate of fairness and teaching the tools for dealing with hot issues fairly is what we want. Dealing fairly with hurt feelings, angry reactions and disruptive disagreements, is the antidote for unresolved hostility. Environments that allow unresolved hostility breed anger, alienation and discontent. Enemies develop over time, they are not the outgrowth of one hostile exchange.

So, when we ask ourselves what is fair, we begin to understand that it is fair to have our bodies, our thoughts and our feelings and our property treated respectfully. It is not fair when they are violated either psychologically or physically. It is fair to confront when we feel we have been mistreated, abused or violated, and it is fair to demand accountability. It is not fair to let mistreatment, abuse and violation go unaddressed, allowing the violators to get away with violation and allowing the violated to build up resentment that feeds hostility, alienation and depression.

It is fair for students to ask adults to help them deal with an abusive situation and expect that the adults will know how to confront each of the parties involved, exact accountability, and even follow up with consequences, if appropriate. It is not fair for adults to tell students to stop being tattle tales, to stop being a baby, just take it, or deal with it themselves. It is fair to teach students how to confront and be accountable. It is not fair to expect that they automatically know how or in some situations that they have the credibility with their peers, to be able to pull off a fair confrontation without some authority figure to help them. It is not fair to let bias and prejudice justify unfairness, persecution or violence. It is fair to confront the biases and prejudices and try to understand how they became part of a person's belief system, and see if the integrity of exposure to the unfairness of the beliefs could help reduce the anger and fear beneath them. In turn, this may at least stop the expression of unfairness and persecution. It is not fair to allow it to continue.

Drawing the Line of Intolerance on Verbal or Physical Abuse

Traditions in a school of allowing verbal or physical abuse to go unaddressed until something really violent occurs must not continue. Hazing falls into this category. Perhaps because we are in the age of xtreme sports and find entertainment in activities that are on the edge of self-destruction, hazing has become less of a rite of passage that is playful and more of a criminal act. The envelope has been pushed to the edge and over the edge. Students die of alcohol poisoning, they are sodomized and raped, all under the guise of good fun and initiation. It is a fine line as students age and want and need more independence, to determine where it's their territory to explore and find their own limits, and where it's over the line and dangerous. When fairness is the measuring stick, and integrity (honesty) is the guide line, the line can be found at least on the outer edge, without much trouble. If someone is being violated, the line has been crossed.

What is a violated line? If we take the topic of hazing, forcing someone to do anything is a violation. For example, forcing alcohol down someone's throat is a violation and should never be allowed, no matter what the age, if fairness is our guide. Pressuring someone to consume alcohol fast or in unlimited quantities is a violation as well. Physical force is not the only force that violates. If the goal is violation, then the entire activity is violating. That applies to every dimension of life. We arrest people for plotting to kidnap or murder someone, even if they never do it, because we consider having violence as a plan and a goal a crime. Verbally abusing another crosses the line. A verbal kick in the stomach is no less violating than a physical one. It should not be tolerated. It becomes much easier to decide when to intervene and when to allow students to work it out with each other, if we use fairness as the guide and violation as the line we don't want crossed.

What Are Fair Expressions of Anger?

What about expressions of anger and what's fair or unfair. Unfortunately, we tend to genderize anger because it is seen as a strong emotion. In this tradition, males are considered masculine when they are angry, and females are considered out of line if they have an angry outburst. As a result, boys are often overly dependent on anger to carry their emotional life. If they are hurt, disappointed, embarrassed, sad or even confused, they may express themselves with anger. This reliance on anger often leads to eruptions of violence. Girls are often punished or at least corrected, for expressing themselves angrily. They are expected to be more controlled, more accepting, more polite, more ladylike. As a result, they often hide their anger and build up resentments inside that come out at a later time in sarcastic or biting remarks. They are expected to express fear or dependence on others to take care of them. As a result, they can become depressed or alienated from themselves or others, or rebel against the stereotype and imitate male outbursts and even resort to violence. Unfortunately, then, each gender has its own obstacles to overcome if they are to have a fair relationship with anger. So, what is a fair relationship?

Anger is as legitimate an emotion as any of our emotions, no more, no less. However, anger, like fear, is a loud emotion that triggers an outward force. Fight or flight is often the phrase used to describe them. Adrenalin agitates and builds up as an explosive force within us. It needs a release. When our reaction to something is anger, we need to be informed by it and respond to it. If, as children, we are taught to pretend we're not angry, we'll have learned a violating approach to anger. By not giving it any expression or release, it has to go underground and smolder within our system. This is unfair to us and violates our system. If we are allowed to have uncontrolled outbursts, we will have learned to be overcome by anger, and it will be in charge of us, rather than we in charge of it. Thus, anger management courses. If we are taught to fear anger, we will be a victim of anger in another way. Intimidated by our own or another's anger, we become its prisoner. We live in fear, and anger controls us. Obviously, none of these approaches to anger is fair. None have integrity. Which is why you are being exposed to self-expression with accountability and its counterpart, confrontation. You are having the opportunity to learn how to express anger fairly and prevent violation and violence.

To express anger fairly, we must be able to first confront ourselves, and ask ourselves why we are angry. As we discover what is being triggered within us that's making us angry, then and only then are we in a position to express that anger. It is always fair to express it with the intensity we feel. It is never fair to use it as a club to beat up someone else. The words we choose to capture the anger we feel are very, very important on many different levels. We want to have the ability to use language well. " O my, that makes me so angry." will never do justice to intense anger. It is not fair because it's too weak and doesn't capture the intensity of the feelings. Using obscenities and threatening to hurt or kill another is an abusive expression of anger. Needless to say, it is not fair either. We want a language of metaphor and strength to capture the intensity of the feelings we have, so they will give us a sense of relief and integrity as we express them. We want to be known and understood even, and at times, especially, when we are angry, and we want to have impact when we express our anger. By mistake, we can think that means hurting, ripping apart or destroying the thing or the person that angered us. However, what we need is articulate, powerful speech. For example: "I am enraged by that comment. You are totally misrepresenting what I said, and twisting it around to use against me. I feel betrayed by you and I'd like to know why."

As a society, we struggle with anger and fairness, but we have not arrived at a fair way to deal with it. In this dawning of the 21st century, we find ourselves in the midst of uncontrolled anger. Road rage, arrests of disruptive passengers on airplanes, car jackings, murderous rampages, school violence on a level we've never known before, all punctuate our landscape. The media both reflects incites and exaggerates this state of uncontrolled national rage. There is no simple solution to this angry state. It is an outgrowth of many factors. However, one essential element runs through every one of those factors: unfairness. If we begin to tackle on the individual level the issues of fairness, we will be making a powerful inroad into our national state of uncontrolled anger and violating ways of expressing anger.

If students in your class can sit next to each other and not be preoccupied with the negative or hostile feelings they have for another, they will be better able to attend to what you are teaching. If when they go home after school, your students are not carrying unresolved hurt or hostility, they will be better able to relate to their family without anger and hostility. In addition, if they learn in school how to confront and be confronted and ask for, as well as give, accountability, instead of harboring resentments or relying on outbursts, students bring a vehicle home that has the potential to influence the family dynamic and change abusive patterns. Together, school and home can become the leadership force in defusing American anger and infusing American estrangement with warmth. Far fetched, you may say. No more so than "lighting one little candle", and a lot more personally empowering.

As was mentioned earlier, fear and anger go together. If we are to commit ourselves to teaching fairness, fear must also be addressed. One of the major sources of fear surrounding fairness, is fear of exposure. Fairness demands exposure. However, we become vulnerable when we reveal what we are thinking or feeling. We fear exposing our vulnerability. We also fear being blamed. Fairness and accountability demand that we take our part, whatever it is, in whatever went wrong. The need to be innocent and free of blame is strong, especially if we are used to being accused, not confronted. If we feel under attack and expect to be blamed and punished, if we "admit" what we did, then fear of revealing the truth and claiming our part, is very loud. Fear tends to bring out defensiveness, lies, manipulation, counterattack, withdrawal, or hiding. It certainly does not foster honest claiming and accountability.

If we consider the incidences of students knowing that a friend was planning a suicide but never told any adult about it and then the suicide occurred, we must ask ourselves why they didn't trust the adults enough to tell them. Somehow, revealing the intentions of a friend's suicide seemed worse than the friend's death. Certainly fear of exposure is present here. Is it the fear of the friend's anger if their secret is revealed? Is it the fear their friend would get in trouble? Is it the fear that adults don't understand and we'd only make it worse?

The same situation has occurred when friends tell each other they plan to hurt or kill someone, a parent, a teacher, a peer. When no one reveals these possibilities to adults, why is the exposure feared? Is there a fear of being ridiculed for believing something that was only said in anger, or in jest? Does fear of embarrassment and looking stupid or scared for no reason, prevent alerting adults to a potential violence? Is the fear of getting the other student in trouble greater than the fear that someone may get hurt or killed? Is there fear of being labeled a tattle tale or a trouble maker? Fear that no one will ever confide in them again if they reveal their concern? Obviously, fear complicates fairness and accountability. If you are going to teach fairness you are going to have to deal with these fears.

What is a fair way to express and deal with fear? First of all, fear must be treated respectfully. It is a powerful and necessary emotion and should not be relegated to the emotion of "sissies". Again we bump into gender and its affect on fear. Boys are to be fearless and girls are allowed and even expected to be fearful. Wrong for both genders. Boys should be as respectful of their fear as they are of their anger, or their hurt, or their desires. It is not wrong to feel fear. It is wrong not to deal with it. Without healthy relationship with fear, boys can go beyond the limits of safety, of respect, of fairness, and endanger themselves or others. They can pretend, lie, hide behind anger, or act out to prove they aren't afraid, all to avoid revealing and dealing with their fear. Bravado, anxiety, self-deception, coldness, indifference, rebellion, delinquency, drug or alcohol abuse can all be the outgrowth of fear.

Girls, on the other hand, can become afraid as a first response to anything new, challenging, dangerous, risky, or hard. They can use fear as a way of getting out of doing something, to get attention, doubting their own ability to take care of themselves or handle difficult situations. Rather than fearless, they can become fearful and dependent on others for protection. This, too, is alienating and can lead to a low self-image, self-doubt and alienation. Or they can reject the stereotype as either gender can, and have a healthy relationship with fear or rebel and become fearless, imitating the male stereotype. Then, verbal and physical abuse may occur, as well as delinquency, pregnancy, and the other hostile forms of alienation.

In either case, the stereotype is not fair to either gender, and you will be confronting those stereotypes when you teach fairness. It takes courage to be fair, to confront and to be accountable. Both genders will need to confront themselves relative to how they relate to fear. Fairness will be a protection for both of them, and eventually, they will learn to realize that and begin to value fairness.

Once fairness is valued, it has the potential to become a powerful positive force. This potential opens the door to effectively teaching integrity, which is the essential ingredient for fairness and the vehicles of fairness, confrontation and accountability. Integrity is, however, a little more nebulous, on some level, to try to explain and teach. However, once fairness is in place, integrity is easier to understand, and its sterling qualities are more recognizable.

By definition, integrity is honesty and truthfulness, and it is wholeness and oneness. In the psychological world, that translates into being truthful about ourselves, about what's happening to us, what reaction we're having, where it takes us, what associations we're making, and therefore, about what we are thinking and feeling. The integrity, honesty and truthfulness, also mean choosing to express these truths fairly and respectfully, and to act and take actions that are true to them. This very complex process leads us to being able to live with integrity. Living with integrity yields the other definition of integrity, wholeness and oneness. The result is a liberated system, whole and at one, free to relate to ourselves and others with honesty and truthfulness.

Just as a work of art, when it is whole and at one, has integrity, so we, when we are whole and at one, have integrity. This integrity is violated by lack of honesty, with ourselves, first, and then, with others. To be honest, we must be respectful and fair as we express our truth. If we violate honesty and fairness, then we violate our own integrity, and cannot be whole and one. Hostility, violence, verbal abuse, denial, lying, defensiveness, all get in the way of our integrity, and, therefore, violate it. The vehicle our system needs in order to maintain this integrity, this honesty, is accountability.

Accountability and its companion, confrontation, complete the circle. We are safe, whole, and free when we are guided by and living in integrity. Whole and at one with our communication system operating truthfully and fairly, we are psychologically liberated. As demanding and challenging as it is, to live out of fairness and integrity, if we learn to choose it and value it, it can become our beacon, our friend, our guide, our protector and our exactor.

The gift of integrity and the fairness it brings, is that every emotion has its legitimate place. We can be angry, discouraged, even despairing at times, hurt, confused, overwhelmed, disappointed, sad, even sometimes depressed, anxious, or afraid. The whole depth and range of emotions are available to us and each one, if we live out of integrity and fairness, expresses the truth of how we are feeling at the time. Each will find its own limit and not dominate us or overcome us, if we are accountable and confrontative, as well as caring and respectful of them. The often misunderstood fact about our communication network, is that it has both an automatic component and a self-participation component. Just because it has an automatic component, we assume that we can do whatever we want to with the information we receive. It's as if the communication system within gives us freedom to process data however we please, because it's how we feel and it's our system. Again, we look to the digestive system for a reality check. If we eat toxic food, it will harm us. If we don't chew our food we will choke. There are ground rules governing how and what we eat and drink even as the system digests food automatically. The same is true for our communication system. There are rules governing how information is received, reacted to, processed and transmitted. Even as the system automatically receives and reacts to messages, there is a sequence and an order to how this occurs and then how the information is processed. We do not have to cognitively know everything, or take charge of everything within our communication system, but we can violate it by being abusive to ourselves or others. Our system will know when it's feeling something and whatever it's feeling, we have to participate in finding out what it is and how to express it and deal with it. It will also know and let us know, if our part in the process of searching, of being self-reflective, confrontative of ourself and accountable to ourselves has integrity.

For example:

If a student is discouraged about doing poorly in class and s/he tells us of the discouragement, we need to give the discouraged feelings their legitimate place and hear the student out, tell the student we're sorry they're feeling like that and we hope something can be worked out to move it to a better place. Notice, that the feelings need to be recognized first, and given care and respect, before any idea of how to deal with them is introduced. We don't want the student to feel unheard by us or the feelings uncared for, yet, we also want to be helpful moving them. If we begin either by saying, "Oh, you shouldn't feel discouraged", or "Well, something needs to be done to change things so you won't be discouraged", we are not giving the feelings a legitimate place. The first statement, "You shouldn't feel discouraged", gives the message the feelings are wrong or the student is wrong.

The second statement trying to solve the situation, if it's our only statement without first acknowledging the feelings, gives the student the impression he/she is a problem to be solved, and if he/she can't be solved, then it sets the student up to feel like a failure. We don't want to communicate to the student either of these messages. They are not preserving the integrity of what is being experienced by the student, and that isn't fair. Yet, responses such as these are very common and can come out of the best of intentions. Nonetheless, they also come out of ignorance of the inner communication system and its (and our) needs. Another reason for learning and then teaching accountability and fairness.

We can often feel afraid of students' strong negative feelings. If we become more familiar with how to deal fairly with feelings, we will be less afraid of them and be better able to help students move through them, instead of getting stuck in them or denying them. This will also contribute to a climate in our classes and with our students, of being respected, known, and understood. Alienation, estrangement and the depressed, anxious or hostile feelings that accompany them are not fostered in this environment. Camaraderie, friendship, intimacy and connections are the natural outgrowth instead. A sense of well-being and safety frees students to concentrate on the tasks at hand. Another way that the positive force of fairness is channeled and exerted, and violence averted.

How Does The Force of Fairness Match The Force of Hostility and Violence?

It will never match it, if integrity cannot be called forth and fairness valued. Much like the pacifism of Ghandi in India or of Martin Luther King in America, the oppressive and unfair practices were changed because the dominant forces (in this case Britain and America) responded eventually to the integrity of fairness. Britain and America philosophically embrace democracy. China does not. Beijing and the brutality toward protesters in Tiananmen Square is a case in point of fairness not prevailing. Squashing the rebellion was considered necessary for safeguarding the authority of the government.

That is why it is so important for schools to philosophically endorse fairness and for administration and faculty to understand, act out of, teach and exact integrity and fairness, from the earliest educational opportunities that children experience. If students get too far over the line of unfairness and live in estrangement and abuse, they will not easily, or in extreme cases, ever, respond to the integrity of fairness. For that small minority of extremists, they must be dealt with on another level, and separated from the school community until some change has occurred within them. Individual interventions will be needed for those few until they are capable and willing to be governed by integrity and fairness. These interventions should be taken as early as possible, since patterns become ingrained and are increasingly difficult to change as students age.

In order for these unresponsive students to even come to our attention early, we must be relating to all of our students in a more intimate ad confrontive way. We must be trying to engage in conversations and to teach accountability and fairness even in kindergarten. World views are being formed, thought processes and interpretation of feelings and how to deal with them and express them are being developed. We want to show them how to process with integrity and fairness. Left unattended as older students, they are resistant to changing their abusive patterns of blaming and judging themselves and others. They sometimes feel that the way they process and think is who they are, and if they change their erroneous patterns of inner communication they will lose their identity. It is much harder to re-teach and change patterns than it is to be part of the formulation process that allows us to teach them while they are first being acquired. Much like language, where poor grammar becomes engrained and re-teaching is difficult and sometimes never really successful, inner language and communication patterns that violate our system and its integrity are more difficult to change than to teach initially.

Nonetheless, only the minority of students will not respond to the integrity of fairness. The majority, even if we don't reach them until adolescence when it becomes markedly more difficult, tend to eventually respond favorably. My experience with adolescent males who were caught in extremely bad communication patterns, even verbal and physical abuse, was that with intense, all school involvement, they found security and comfort in fairness. When the positive force of fairness met students caught in the destructive force of alienation, out of control emotions, and self-doubt bordering on self-loathing, fairness won most of them over. They were won over, not by dominance and fear, but by invitation and example. The force of confrontation with accountability being exacted of parents, students, faculty and administration, was so strongly attractive and yielded such wonderful outcomes, even the hardened tended to respond. Their fears were reduced. Their need to avenge, rebel, hide, manipulate, destroy, yielded to their greater need to feel safe, known, respected, understood, successful, worthy and on track.

The power of fairness and the integrity of fairness lies in its draw for us. We are, by nature, drawn to integrity, to truth and honesty, because we are, by nature, born with integrity, whole and at one. As we age and develop, we become capable of participating in the integrity of our communication system, either maintaining our integrity or violating it. If we grow up in an environment that fosters fear and the need for protection, we develop patterns of defensiveness, hostility, deception, manipulation or withdrawal. This violates the integrity of our system and our need for intimacy and for the safety of integrity and fairness.

Students come to us from every kind of home and background. Just as we try to see that our youngest students have breakfast before they start school, and we try to provide enrichment for deprived students, so we need to communicate with fairness and integrity. We must teach them fairness, and how to communicate fairly. Only then are they in a position to value fairness and its power to protect them even as they are exposed and known.

When we get caught in thinking that the heat and drama that anger and hostility generate are more powerful than the heat and positive draw of fairness that yields understanding, intimacy and care, we need to look at the way we define power. There are two ways to define power, and it's time we included both and selected the appropriate one for the inner world's communication network.

Traditionally, power is thought of as the force to dominate, conquer, control and win. The most powerful military force is the one that conquers the enemy. The most powerful sports team dominates the sport and wins. In the battle with disease, the most powerful force is either the disease that kills, or the person who conquers it and lives. In the battle of the sexes, men are, for the most part, physically stronger than women and they are seen as more powerful and the dominant sex. In this view of power, battle imagery is the predominant theme, anger is a dominant emotion, and winning is the desired outcome. There is a certain need for hostility to fuel this fire, and rivals can become enemies. Winners and losers emerge, and success or failure is defined in terms of dominance. It is a hierarchical set-up where winners are superior to losers, success is superior to failure, and the dominant are superior to the dominated. Self-worth is tied to dominance.

Taken to its extreme, power seen as the measure of the force to dominate, can breed hostility and violence. Rivals can become enemies to be destroyed, wrongs need to be avenged, and dominance must be restored. We are experiencing the price of this orientation to power in our country, on our roads, at our workplaces, and in our schools. The continuum of power as the ability to dominate, conquer and control is currently weighted toward the extreme. As a nation, we are not happy with this trend, but we are uncertain how to address it or reverse it. One very significant place to start, is with our definition of power and our extreme reliance on force used to conquer and control. If this approach dominates our thinking, it cultivates hostility and breeds unfairness and violence.

Another way of viewing power is purely as force, as energy. That is the approach of physics, and it is free of the bias that force as dominance cultivates, the bias that opposition requires hostility. Force as force, is force as energy. The reliance on anger and hostility is not relevant. Desire is the source of our energy. Conquest and control are not the built-in goals, rather, movement is. Power as energy is power as movement. The ability to move, whether it's ideas, thoughts, feelings or imaginings or whether it's making things happen, movement becomes the ability to exercise power. This is an exciting difference. Strength can now be measured in terms of intensity. In the psychological world, that gets translated into intensity of desire. The stronger the desire, the more intense it is. The stronger, more intense, our desire, the greater the force. With this definition of power, and strength, fairness can now become a powerful force for movement. If valued and strongly desired, fairness becomes a strong force. Since fairness is not achieved through conquest and does not depend on establishing winners and losers, the integrity of fairness is the natural governor of movement. If it is fair, then movement should be in that direction. If it's unfair, movement should stop and be re-directed toward the fair position.

This approach to power is revolutionary in its force, its effectiveness. I once was having a discussion on accountability and fairness with a small group of about 8 - 10 adolescent males, and one of the boys began sharing with the group. He told them he had been in a serious car accident a few years ago and that an injury to his head now causes him to have seizures. This condition, he said, made him very fearful and anxious about any blow to his head. With that, one of the other members of the group blurted out that he was so sorry that in fooling around the night before he had hit him in the head and they had gotten into an angry exchange. Now, he said, he could understand why the anger was so quick and loud. Overcome with the realization of how terrible it must be to fear having a seizure, the boy jumped up and went over to the injured boy and put his arm around his shoulder and said he would make sure never to go near his head again. There was total silence in the room as the two boys acknowledged where they each were and then embraced. We were all moved by the depth of intimacy and the caring that we were witnessing. This depth of feeling generated great intensity and this intensity generated movement toward the depth of intimacy that occurred. We were together in a reverent moment.

This example dramatically shows the power of fairness and the movement it generates. The unfairness in this scenario was: 1) The injured boy's unexplained angry reaction the night before. 2) The angry response of the boy who got the angry reaction when he knocked the injured boy in the head that night. The movement that occurred through the fairness of the exchange in the group the next day was: 1) The injured boy moved out of silence and of hiding his fear, to sharing his story and revealing his fear. 2) The other boy's movement to respond with care and apology as he heard the story and the fear. 3) The injured boy's movement in accepting the care and apology. 4) The physical movement of the other boy of going over to the injured boy and embracing him. 5) The injured boy's movement to receive the gesture and emotionally join the other boy in the intimacy of the moment. 6) The movement of the group to respectful silence and to allow the intimacy of the moment to move them as well.

Once we apply the definition of power as force, as energy, to our communication network within, we are in a position to feel the energy of expressed thoughts and feelings and be moved by it and them. Once we let go of the definition of power as the ability to conquer and control, the purpose of exercising power changes and the process of moving comes to the fore.

When we introduce fairness and the integrity of fairness to our communication with accountability process, the exercising of power through self-expression has built-in guidelines for the process and for the outcome. The process, to be fair, must treat with respect every thought and feeling being expressed. Every thought and feeling must be expressed without attacking, blaming, ridiculing. In other words, messages must be expressed fairly, not violently or abusively. The goal of the speaker is to be understood, not to be superior or to intimidate. The goal of the listener is to understand, not judge or blame. Out of this fair exchange of information and understanding, should come fair and respectful dialogue that leads to being known, not being dismissed or destroyed. The movement of heart and mind, feelings and thoughts, when governed by fairness, yields connectedness, intimacy, and friendship that is marked by respect, caring and generosity of spirit.

Capturing the positive force of fairness to prevent the negative force of violence hinges on shifting the focus away from conquest and away from hostility and anger toward a focus on discovery and understanding, and toward respect and care. When we started this discussion of fairness, the complexity of fairness was introduced. Hopefully now you are in a position to better understand what that complexity entails. Now let's explore further its power.

The Powerful Effect Fairness Can Have on Students, A Classroom, A School

As I have illustrated, the climate of fairness creates a sense of security for students. This security, in turn, creates a climate of openness. Students who feel protected and safe relate far differently with each other than students who are jockeying for positions of power and dominance over each other. The openness that comes with the safety of fairness has a friendly warmth and lightness to it, that allows students to relax with each other, share with each other, and connect with each other in a wholesome and intimate way. Provided with the tools of integrity and fairness, which are confrontation and accountability, students do not need to fear being ridiculed, intimidated or abused. They know that such behavior will not be tolerated. Either they will confront it or be confronted with it, and, when needed, the faculty and administration will add their weight to the confrontation. Regardless, accountability will always be demanded, and fairness will be restored.

This predictability is one of the key ingredients of fairness. Every legitimate confrontation of unfairness must be addressed and dealt with fairly. Students can not and will not feel safe if accountability is allowed to be casually enforced. They must trust that we are committed to providing them with a safe environment and that it is not a random condition. It is not a coincidence that at a time when metal detectors, locked doors, and armed policemen are becoming necessary school precautions to physically protect our students, we are discussing how to psychologically protect our students. These two dimensions are totally interrelated. Again a chicken and egg dilemma. Physical violence comes out of hostility, anger, alienation and fear. Hostility, anger, alienation and fear are all psychological factors that breed physical violence. So the circle needs to be interrupted on both dimensions, physical and psychological, to assure safety. If students aren't physically safe or don't feel physically safe, they can not and are not going to be psychologically open. If they aren't psychologically open they can't deal with their hostility, anger, alienation or fear. If they don't deal with their hostility, anger, alienation or fear, they will be trapped in those feelings and may encounter violence or be violent. So, both physical and psychological protection are needed. Fairness provides psychological protection, and confrontation and accountability provide fairness.

A school that must now rely on metal detectors and armed guards, is in a crisis situation. Psychological protection must accompany physical protection or safety will never really be achieved. A school that is not fearful of physical violence is in an opportunity situation. It can focus on teaching fairness and self-expression with accountability. Psychological safety will lead to openness and sharing, warmth and connectedness. Not only will physical safety be expected, but psychological intimacy and well-being can be achieved. Then both physical and psychological safety will be present and the school will be truly providing an educational environment.

Let us make no mistake, achievement correlates with a student's sense of well-being and safety. We can do as much national testing as we want, hire more teachers, require greater proficiency from all teachers, and even shrink class size, and still not get the results we're looking for, if we don't also address the climate and educational environment in our schools. If students are alienated from themselves, each other, and/or the teachers, they will be alienated from learning as well. If students are angry and hostile, they will have disruption, not education on their mind. If students are fearful and insecure, they will be too distracted to apply themselves fully to learning. Teaching students self-expression with fairness and accountability is not just an interesting elective, it is an essential ingredient for creating a fertile educational environment for all our students.

Obviously, our concern and upset with our students' attitudes and performance on standardized tests, is not focussed on those students who are already successfully learning and achieving. Our concern and upset is with the rest who are underachieving, failing, acting out or dropping out. For them to get on board, fairness and accountability are essential. For the others, it is enriching. For the educational community it is a wonderful opportunity.

If we look closer at alienation and the by-products that fairness must confront, let's begin with verbal abuse. Both teachers and students may be the victims or the perpetrators of verbal abuse. The issue of teachers being expected to speak with accountability and fairness is not one easily addressed. Adults, especially those in authority, tend to think accountability is for those under their jurisdiction, but not something that should apply to them. Teachers have authority over students and often teachers think their authority will be jeopardized if they are confronted fairly by students. Ironically, their authority is enhanced if they are accountable, because students respect them for it.

Teachers have the potential to have a dramatic effect on their students' self-image, self-confidence, aspirations and achievements. However, that potential can go either way. A student can be devastated, hurt, humiliated, shut-down, or discouraged by a teacher's comments, even as a student can be inspired, proud, eager to participate, or excited to excel because of them. You have a serious obligation to be fair and respectful with your speech, and accountable when you're not. You also have an obligation to demand accountability from your students. The climate in your classroom is under your leadership. You can't tolerate verbal abuse directed at you or at other students. You have the authority to demand accountability, not just about school work but about relationships with you and each other. The fact that students can confront you speaks to equal rights and the equal right to be treated fairly and respectfully, not to weakening your authority.

For example, you are at the end of your rope, a student makes a disruptive remark, you lose your temper and tear into the student. Understandable, because you're only human, but not acceptable. Either you should catch yourself and confront yourself, or the student or one of the other students, should confront you. Your response should be reflective and honest, claiming your intense frustration. Then it should contain an apology for lashing out at the student followed by a rephrasing of what you wish you had said. Confronting the student fairly, the student should be in a position to apologize for the behavior that started it all. If the student's apology doesn't come unsolicited, you would need to confront the student further and ask what's going on for the student that this attitude is present. Now, hopefully, the conversation turns to where it needed to be originally, to the student's out of line behavior. Other students may join in confronting him/her, and fair peer pressure will be exerted. A certain amount of revealing should occur, such as the student admits he had words with a friend before class and is now taking it out on you, or that something upsetting happened with another teacher and it's put the student in a bad mood toward teachers. Whatever the story, hopefully, there would be something forthcoming so that you could say that you understand how it happened to both of you, and after each apologizing, the class proceeds in a unified way. No one is left distracted by jarred nerves because of an unresolved heated exchange. Instead, they have experienced a clash, a fair confrontation and a resolution.

This kind of accountability by teachers sets a wonderful example and gives students a sense of safety because verbal abuse isn't tolerated, even if it's a teacher, and when it's dealt with, it's done fairly and respectfully and usually gets resolved on the spot. If it's a more serious situation and requires additional attention outside of class, they will also be assured if they know it's not allowed to drop, but is addressed until it's resolved.

If the offending student doesn't become accountable but still is abusive, then appropriate consequences need to be imposed. Even if it's a teacher who isn't accountable and continues to be verbally abusive, there needs to be consequences. The power of fairness is in its fairness. Abuse hasn't been dealt with effectively and fairly until it is stopped.

Bullying and bullies must not be tolerated. It and they must be stopped. Fairness demands it. If verbal abuse is dealt with as it occurs, physical abuse is less apt to occur. But if it does, it, too, must be confronted fairly, accountability exacted, and appropriate consequences need to be meted out if the abusive behavior doesn't stop. Appropriate means less severe to severe, depending on the offense and the refusal to stop. If a student doesn't or can't stop, an intervention should occur, ranging from counseling to placing them in an alternative setting. Other students will feel relieved that action is taken and the abuse is not tolerated. Fear and alienation will be much less likely.

Finally, the powerful effect fairness can have on students is also found in their willingness to confront each other. Instead of tolerating verbal or physical abuse or threats, they, too, become intolerant of violation. They also learn how to confront fairly, so they become more skilled and more comfortable with it. If confronting on their own doesn't work, they are more willing to seek help from teachers and administrators. The trust that fairness yields brings about an attitude of seeing teachers as someone who can be helpful. If we think of the suicides that friends knew were being considered or planned but never shared with the adults in their lives, we should be grateful that fairness may allow students to trust us and, therefore, tell us what they know. Their worries, if shared with us, can be addressed together with them. Not only might a life be saved, but a sense of community is formed. Watching out for each other creates a warm, supportive feeling that can only enhance the student's desire and ability to learn. Achievement can become exciting once education is not considered the boring part of school, but rather the common bond among teachers and students. Learning how to communicate fairly with themselves and others brings a self-confidence and sense of well-being that maximizes their ability and desire to learn. Everyone benefits, which, of course, is the essence of fairness.

Activities:

- Have a round table discussion on fairness and the challenge it poses for you as a person and as a teacher.

- Select an article from the newspaper or TV reporting on a situation where verbal or physical abuse occurred, or choose a television forum where verbal abuse occurs among the participants, and write an essay on what wasn't fair about the way the abuse was dealt with, and how confrontation with accountability would have changed the dynamic, and the outcome.

- Write a paper on the effect a teacher's words and behavior had on you and on the class, when you were a child, either in a positive or negative way. Discuss the fairness issue as it relates to this teacher and why the effect of this teacher on you was so strong. Read each other's papers and then discuss the themes that ran through them.

- Have a panel discussion on the climate of the school you attended, the presence of verbal or physical abuse, the role of fairness, of confrontation and accountability, and the dominant energy in the school. Explore what you felt or noticed relative to alienation and achievement. Discuss whether school was a good experience for you and how it affected your desire to be a teacher.

- Break into small groups and create a scenario where a teacher is verbally abusive and is confronted. Play it both ways, where the teacher is accountable and where the teacher is not. Resolve the situation and determine consequences. Enact them in class and discuss how you would feel in those situations and how you'd deal with them.

- Break into small groups and role play confronting some students and have students confront each other. Have the teacher be one who knows how to fairly confront and ask for accountability. Discuss the various ways the role of teacher was enacted and which were the most effective and why. Which were the least effective and why. Discuss the complexity of the role of the teacher when she is facilitating a confrontation and exacting fairness and accountability.

|