Book Chapter: The Power of Language

© 2000 Michele Toomey, PhD

Words can inform our mind, caress and comfort our feelings, excite and thrill our spirit, or warm and kindle the flame of our hearts. They can also slap our face, punch us in the stomach, rattle our nerves, kill our desire, or destroy our self-confidence. Of course, this is metaphorical, but these metaphors capture in words our physical reactions to what is said, and that is the power of language. It has profound effects on us.

Language, therefore, is either a powerful instrument or a dangerous weapon. When children turn 16 and are allowed to drive a car, a powerful vehicle that can provide ease in transportation, or pleasure in a ride, can also become a weapon of destruction. Before we allow children to get behind the wheel, however, we issue learner's permits, provide formal courses in driver's training, and then test them before giving them a license to drive. We recognize the power of driving a car. We do not recognize the power of language.

Bullies usually escape punishment if they are clever enough to limit themselves to verbal abuse. Words do not leave physical bruises and broken bones that prove the presence of abuse. Verbal violation is invisible to the naked eye, but it is no less damaging to our self-image, nor less painful for our spirit. By denying the power of words we have not protected either our children or ourselves. Instead, we have left it to chance, to good manners, to correct grammar, and to religion to provide us with the formula for the proper use of language as self-expression. For powerful speech, we turn to orators, ordained clergy, poets, playwrights, actors, writers. We, the people, are just expected to use language much as we use a bus. We should know the system, follow the prescribed procedures, use it to get to our desired destination, and then get on with life.

Ironically, the exchange of words is a major portion of that life, and has a definite influence on its quality and on the direction it takes. The texture and fabric of our lives are affected by the way we communicate with ourselves and with each other. Think of how we were influenced in childhood by a parent or teacher, relative or friend, who commented on our appearance, our intelligence, our temperament, or our fears and desires. How many of us can remember being told something about ourselves that either motivated us to dare follow a dream, or squashed our hopes before we even tried. How many of us confronted that person and told them the effect their words had on us?

Inspiration and devastation can both be achieved with words. Relationships can be both cultivated and stifled by words. There is no justification for denying the power of language. Yet, children are not taught how to process what they are thinking and feeling, and then formulate the words to describe it. They are frequently taught to conform to a pre-defined way of thinking, feeling and interpreting. Gender, religion, race, nationality, social class, all have their prescribed approaches and norms. Rarely are children taught how to process what they're thinking and feeling by looking at themselves.

Children may react automatically or not react at all. They may have been allowed to react anyway they chose or told they were wrong in how they reacted, or they may react as expected. However, after their initial reaction they need to ask themselves what this reaction is telling them about their relationship to themselves and to this particular situation. Left untaught, they may learn to rebel, judge themselves or others, analyze, ignore, deny, deceive, manipulate or abuse. Usually no one formally looks at the way they are receiving messages and responding within themselves "to" words and "with" words. They are left to their own devices and they develop their own world view from listening and observing, choosing whether to comply or perhaps just unknowingly following what they think is the path that language should take.

Integrity is the key word in learning to use the power of language, for without it, the power is abused. Integrity, or honesty, in self-expression, eliminates deception, manipulation, judgmental accusations, abusive tongue lashings, and lying. Our orientation toward this communication system, therefore, must be to preserve its integrity by being respectful and honest with the information that gets transmitted through it. We must have the intention of using the information to gain clarity and to understand better what is being said, so that we can relate to it and to the person providing the information with respect and caring.

For example:

Conversations rarely take place that explore how students feel about eating lunch at 10:30 a.m. because the cafeteria is too small and someone must eat early. It is seen as expedient. They are to conform. How they feel is not considered relevant to what they eat, if they eat, or if they enjoy eating lunch. The focus may be on their behavior. If they go to the cafeteria, or if they are polite and don't cause trouble, they are seen as doing well. There is no time and no perceived necessity to try to discover how they are experiencing lunch time. However, that is a mistake.

We may never know how they are being impacted, unless they act out and get into trouble. Even then, we may or may not discover what's going on for them. We may just make them stop. They may refuse to reveal. Whether they call attention to themselves or not, we should explore their inner thoughts and feelings, helping them get in touch with themselves, teaching them how to express what they discover, and then how to deal with it.

By treating respectfully and fairly whatever they tell us, they learn it's safe to reveal themselves, and the next time they have something to share there's a little better chance that they will. Over time, open revealing of their inner world becomes a natural routine, and they are better known by themselves and by others. This connectedness, this intimacy, creates the climate of desire to relate with fairness and respect because we now know who the other person is, not just what they say or do.

The example of lunch time is a good one, because lunch is a very social time for children. Conversations that explore how they are feeling about themselves at lunch relative to who they sit with, who talks to them and who doesn't, how they are treated and how they treat others, should be an integral part of their conversation. Unfortunately, unless there's a physical or loud encounter, the question of comfort and belonging, probably doesn't ever come up. Yet, it should. Our children are too often experiencing their life's upsets, struggles, or worries on their own.

Powerful feelings and reactions are affecting our children and, for the most part, they are left unexplored, and children are left alone to deal with them. Alone, but not unaffected. Silent, but not without feelings and thoughts that need to be expressed, received and respected. Children need to be taught how to deal with these feelings and thoughts in a psychologically fair way, if they are to be connected with themselves, their life, and with others.

Why Teach Self-expression?

Self expression is vital to our happiness, yet it is not taught. We are expected to just know how to capture in words what we are feeling and thinking. Why we assume that just by learning to talk we can automatically know the complex process of self-expression is beyond me. We, who in a split second, are able to make associations with something that we experienced in the past or anticipate might happen in the future but that got triggered by something that's happening in the present, are not simple to describe.

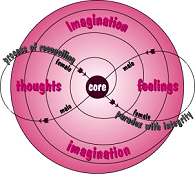

We live in three time periods: past, present and future. We have three dimensions: thoughts, feelings and imaginings, and we operate on at least three levels: the conscious, unconscious and sub-conscious. Yet, we speak and hear only one word at a time. We are a body and a spirit and experience life through the body informed by and informing the spirit. We are, by nature, paradoxical, and we are forever trying to reconcile wanting and not wanting to say or do something. Add to that the fact that no one can see or hear our inner world with its communication network that receives and transmits our thoughts, feelings and imaginings and we have true complexity. We live in and communicate from this sophisticated invisible inner world with its complex communication system. How we express ourselves is our only way in, around or out of this invisible world and its system.

A curriculum that only teaches our children "subjects" and doesn't teach them about themselves, and how to process, discover and express what they are thinking and feeling, leaves our children's relationship to what's happening to them out of the educational process. It gives them the impression they are meant to know things, to have ideas, to think and reflect intellectually about information, but not to give a priority to how anything is affecting them. Information within themselves and about themselves is not considered as important as other information.

Self-expression with accountability asks us to make information about ourselves as important, and often more important, as information about anything else. Then it asks us to learn how to deal fairly and accountably with whatever we discover about ourselves, and finally, to learn how to express with integrity and fairness, what we've discovered. It teaches us how to participate in the power of self-expression as an exchange of information about ourselves, by teaching us how to confront ourselves and then express what we discover. It yields honesty (integrity), and fairness, which leads to being known and trying to know others, feeling connected to ourselves and trying to connect with others. This intimacy and desire for intimacy allow us to live our lives with warmth and a sense of understanding and well-being. Alienation and the coldness it brings or the eventual hostility and violence it can evoke, are never the products of this approach. Intimacy is.

The Nature of Our Communication Network

The communication network within the self is very complex. Therefore, if we are to learn to use the power of speech with integrity and accountability, we must learn the rules that govern that network. Just as we learn the rules governing access to the information on the internet, the inner network of the self's communication system has rules. We take them for granted, because it's our inner world, but, it's a system that we participate in, even as it's a self-governed system. Just as digestion is self-governed, what we eat, how we eat, and the way we are feeling when we eat, also affect our digestion. We, therefore, play a critical part in our nutrition and our digestive system. The same is true of the communication system within our body. Messages are automatically received and sent without our deliberate involvement, yet, how we feel when we receive these messages, how we react to them, how we process them and how we formulate new messages, all play a critical part in how we are affected by them and how we deal with them.

With today's high tech equipment, it is possible to trace messages traveling through our system. Colored images of messages being transmitted to and from the brain show that emotionally "hot" data, highly charged data, has a different effect on us and on our brain than neutral data. It is possible to see the brain "working", and if the tasks are complex, to see that they take more energy. Tasks that become routine, even complex ones, are shown to take less energy than new ones. Brain activity also indicates that anger, fear, frustration and stress affect our system differently than joy, excitement and eagerness. The former create stress that costs energy, while the latter replenish energy. We actually have evidence of the powerful impact information has on us, yet we still place little importance on teaching it.

Our communication network transmits physiological messages, intellectual messages and metaphorical messages that we visualize with our mind's eye or hear with our mind's ears. It also stores messages that can be triggered automatically or be deliberately recalled. Such a complex system has to have a complex capacity to translate these multi-dimensional messages into a common language.

They all get sent to various parts of our brain where they are received, and if our system is in good working order, this part of the communication process is done automatically. So far so good. However, in addition to this automatic system, we are able to participate in the communication process, and now comes the real complexity ... our involvement. We can interpret, react, reflect, process, evaluate, judge, translate, and make associations on everything and anything that enters our system.

A big alert should now be beeping on our screen, because if we don't learn how to participate in the integrity of this system without breaking the rules, we will not be able to communicate the truth of who we are, what we are experiencing, or what we need. This processing of psychological information that contains feelings as well as thoughts can be violated very easily, so it is of utmost importance that we learn the rules of the system and how it functions.

Our communication network functions in the following way:

- A message is received, either from ourselves or from another.

- It triggers a spontaneous reaction that has emotional feelings in it that have been shaped by our past and by our degree of investment in the information.

- That reaction, along with the message that triggered it, now goes through our system with a "charge" attached to it:

negative: fear, anger, frustration, disappointment, etc

positive: excitement, desire, attachment, pleasure, etc.

neutral: indifference, disinterest, lack of involvement

If it is strongly negative or positive, it is "highly charged". The more highly charged message travels through our network with greater intensity. The greater the intensity the more "heat" it generates, causing the system to speed up and search to understand what's happening as it experiences strong emotional response.

Once a reaction is registered and its intensity is felt, the message and our reaction to it must be processed. Processed is not judged, not just reacted to again and again, and not just analyzed or solved. Processing information means making connections and associations that give us insight into our reaction and response to a message, when we proceed to reflect on what we discover and then formulate a position and a response. Processing information is more complicated when the message is "hot" or highly charged. The intensity brings an urgency and a speed with it that triggers associations, ideas and reflections that are also hot. It also takes greater discipline to process "hot" messages, because the urgency and intensity may excite us to only react to our reaction, setting up a chain reaction. If we get caught in a chain reaction we need to be able to recognize the chain reaction, gather insight from it and then relate it back to the initial message, and then process them all.

- Processing information allows us to use our imagination to travel through our three time zones of the past, present, and anticipated future to look for associations and memories that add clarity and complexity to our reactions to the message. This clarity and complexity give us depth and greater understanding and intimacy with ourselves.

- As we process, we are to reflect on what we have discovered from the search. Then as we better understand how we are relating to this information, we are ready to formulate our relationship to the message and the position we are taking relative to it. Our relationship to a message is the most intimate dimension of our communication system. The more clarity and complexity we've gained in the process the more insight and intimacy we have with ourselves.

- We then articulate either to ourselves or to another the complexity of how we are relating to the message, and that is self-expression with accountability. It is an honest expression of what we think and feel and understand about our relationship to the message and it allows others to now be connected and intimate with us.

- This process of sending and receiving, reacting to and processing information without hostility, judgment or deception is the way to participate in our communication system without violating it. The goal is discovery, understanding, intimacy and integrity, not judgment or control.

What Violates Our Communication System?

We can violate our system in several ways: by deceiving ourselves about how we are relating to the data, by judging either the message or our reaction to it, or by reacting to our reaction. Deception violates the system because now we can't discover the truth about our relationship to the message. There are lies and therefore, error in the system. Judging violates the system because it violates the purpose of the communication network which is designed to connect us to the information and to ourselves. If we judge we add a layer of good or bad, right or wrong to what we're thinking or feeling, and that skews our search to either justify how we feel or make a case against it, instead of engaging in an honest search for understanding. Both deceiving and judging our reactions interfere with our ability to be true to ourselves and to be ourselves. They prevent intimacy and understanding. Reacting to our reactions never gives us a chance to process and reflect on our reactions, so it violates our system because we cannot connect with it with any choice. We have lost choice and are out of control.

Think of situations where you felt affronted, embarrassed, awkward, disappointed, angry or afraid and didn't let yourself feel these feelings, or pretended you didn't feel them, or judged them and tried to change what you felt, or reacted to them with another reaction and didn't let yourself process what you felt. It left you unable to connect with yourself, and certainly unable to express yourself with any integrity or intimacy.

Are you beginning to understand why communication is such a complex process? There is a sophisticated information network within us, and there are innumerable ways to get off track, to get lost, to misinterpret, to distort and misuse the information. Just learning to talk and to think is not enough. We must learn to process the messages we receive and then express them. If it's that complex to communicate with ourselves it is, of course, even more complex to communicate with others. Now we have the added layer of not wanting to hurt another's feelings, wanting approval, or not feeling sure how to say what we're feeling and thinking. Or there are the layers of wanting to counterattack, wanting to hurt or ridicule, wanting to crush or diminish the other and not having the discipline or desire to contain ourselves, or the courage to confront rather than attack. To prevent hostility and violence, we need to hear and then respond, or speak and then be heard, with integrity (honesty), fairness and respect. When our messages are received or sent with hostility or defensively, or hurled back at us distorted and attacking as a weapon, the integrity of the system is violated. We need the skill and the courage to confront this abuse and to ask for accountability, either of ourselves or of another, or both.

Confrontation and accountability are the vehicles that preserve the integrity of the communication network and allow us to have fair and respectful conversations with ourselves and with each other. As a result, clarity, understanding and the intimacy that comes from the exchange yields true communication. However, our communication system is very complex, and if we want intimacy and liberation (the freedom to choose intimacy) we must learn how to participate in our very complex system without violating it or ourselves.

If we follow the analogy of the digestive system and the rules that govern it, we are taught how to play by those rules: to chew our food carefully, not to over-fill our mouth, and not to guzzle liquids. We are taught what foods are toxic and could poison or kill us, what constitutes a healthy diet, and how body weight and health are affected by what we eat. We learn to balance the pleasure of eating with the health of eating. Indulgence and abstinence are taught as the paradox of the gratification of pleasure and the need for healthy boundaries. We even recognize the impact of body image on our self-image. At least we get the general idea that there are rules that govern this system, and that violating those rules has consequences.

In reality, we could do a much better job of teaching our children the importance of an informed relationship with food and drink. The powerful effect, both physiological and psychological, that our relationship to food has on our life warrants more attention in our curriculum, but, still, our participation in nutrition and the digestive system gets far more attention than our participation in the psychological integrity of our communication system.

Since communication has such a powerful effect on us, one of the greatest dangers to us and to others, is when we violate the integrity of our communication system. What does that actually mean? It means we need to learn to follow and to teach the rules governing that system, so that whenever we participate in it we do not violate it or ourselves. The estrangement, alienation, anxiety, depression and/or hostility that result from a violated system, cause great suffering and often trigger violence. As teachers, you will be a powerful voice in your students' lives, so it is critical that you both know how to express yourself with accountability and that you teach your students how as well.

A Closer Look at The Impact of A Violated System on Us

One very significant difference between our inner communication network and any other network however, is the fact that when we receive a message we are affected by it. Not so a telecommunication network. It is just a conduit for the messages. We are not just conduits. We react to and relate to messages. Again, our communication system parallels the digestive system. When we eat food it affects us. Some foods are desired, some are not, some are good for us, some are not, some make us edgy, some do not. The same is true for words. The fact that information affects us, complicates the transmission of messages. The reaction and subsequent relationship we have to the messages we receive determine both how we receive them, how we interpret them, and how we respond to them.

It is important to remember that we receive and react to messages almost simultaneously. When a message enters our system it triggers an automatic reaction. This reaction is a spontaneous response that happens in a split second. It is not a cognitive act. It is an unconscious association that our system makes on its own. Often we aren't even aware of the connection being made with memories of experiences from our past.

Once when I was driving from Cambridge, Massachusetts into Boston, I began to feel nauseous and I couldn't understand why. Suddenly it came to me. I had undergone chemotherapy at Boston's Peter Bent Brigham Hospital while I was a graduate student at Harvard. This road was the one I took when I went for a treatment, and I was always very nauseous when I rode back to my apartment in Cambridge after the chemotherapy. My unconscious had made the association with the road and nausea, and triggered a physical reaction. Once I made the connection, the nausea passed. This experience was such a dramatic example of the speed of unconscious associations being triggered and setting off a reaction to a message that the conscious self wasn't even aware of receiving. In this instance it was a place and a feeling. It could be a smell, a touch, a sound, an action, or a verbal message.

Another time, one of my 16 year old students was being confronted for hitting another student. When we explored what was going on we discovered that the student being hit (a tall but slight boy) was being sarcastic to the boy doing the hitting (a large, heavy set boy). They then revealed that each of them was reacting the way they reacted at home to the same behavior. The slight boy was physically bullied by older brothers at home and they were so much stronger and bigger than he was, the only defense he felt he had was sarcasm, so he verbally punched them with ridicule. The physically larger boy was ridiculed with sarcasm at home, and he reacted by physically punching. Both boys were associating the behavior at school with the behavior at home and reacting to it in the same way. Once they realized that, they apologized to each other. They didn't want to continue the pattern from home that they hated. Now that they understood what had happened, they could begin to change. This confrontation and the revealing of associations that were being unconsciously made by each boy, did, indeed, change their pattern of relating.

The first thing we have to learn, therefore, about participating in our communication system with integrity, is how to deal with our reactions. Remembering that integrity means both honesty and wholeness, we must try to discover the truth about our reaction so that we can be honest with ourselves about it. Then we must decide how to deal respectfully with that truth, so that we can preserve the wholeness of our system. By dealing honestly and respectfully with our reactions within our system, we can then express ourselves to others outside our system in the same way, without violating them or ourselves.

Too often, we are not taught how to deal respectfully with our reactions, and the integrity of our communication network is compromised from the outset, This can occur in one of three ways or any combination of them:

- Our reaction is strong and triggers a chain of reactions and we only react, never reflecting on what is going on for us.

- Our reaction is strong and we try to stifle it, deny it, hide it and refuse to allow ourselves to legitimize it or express it, so we never reflect on it.

- Our reaction is strong and we don't claim it as ours but instead blame whatever or whomever triggered it for being the cause of it, projecting our reaction onto others and never looking at ourselves.

In all three of these cases, self-reflection and the self-awareness and discovery that it should yield, never occurs. Consequently, the communication network is not only compromised, the process is aborted. Reactions are meant to be only the first response to a message, not the only response. Without reflection and processing, the reaction leaves us unsettled and on edge, thus vulnerable to some other message that might have the potential to trigger us.

The following are examples of the three erroneous ways to deal with reactions.

- A chain reaction and how its force is eruptive and disruptive with the potential to violate:

Julie overhears her friends commenting laughingly on how "stupid" she looks in the outfit she has on. She is hurt, embarrassed, and angry and reacts by bursting in on their conversation and letting them have it. They react defensively and she just continues to react, getting louder and angrier. They now feel justified in getting angry back, so they react angrily. In the end, if all they do is react, one or the other must either resort to violence, physical or verbal, or storm away. Neither group has been accountable. Everyone has been reactionary. Nothing gets resolved and nothing is discovered or understood. This is an example of a chain reaction.

Self-expression with accountability would have allowed the scenario to go more like this:

Once Julie overheard her friends ridiculing her appearance, and she reacted with hurt, embarrassment and anger, she'd confront herself first, asking herself why she was reacting so strongly. She might discover that she thought she looked "cool" in her outfit and her self-image was shaky about her appearance at this point in her adolescence, so it really hurt and embarrassed her to be laughed at behind her back by her friends. She might also realize that what angered her was the fact that they didn't tell her what they thought, but used ridiculing her as their bond.

So, now as she approaches them to confront them, she's ready to reveal how she feels about their comments, and how she feels about their talking behind her back as a way of connecting with each other at her expense.

Having been self-reflective and processed her reactions, Julie would have her integrity intact and be on solid ground with herself. Her friends could still react defensively, but if they did, she should just repeat her points and confront them again. At that point, some or all might be accountable, apologize, and then reveal why they fell into gossiping about her instead of confronting her. In the best of all options, they would all have claimed what was going on for them and would have learned something about themselves and each other, and understand better the consequences of their words and actions. They would then feel relieved from the encounter and once the confrontation was over the conversation that followed would in all probability include an apology. There would be growth, accountability, and intimacy.

- If we use this same example, but the reaction is one of denying and refusing to deal with the strong reaction to the gossip, it might go like this:

Julie reacts by getting red faced and all hot inside with hurt, embarrassment and anger, but refuses to deal with the feelings. She chokes down tears and/or the urge to blast her friends, and quickly leaves the area. Once out of sight and out of earshot, she presses against her strong reactions and reacts strongly back to gain control. She tries to act like nothing has happened and won't allow herself to feel or think anything except how to shut herself down.

When she sees her friends, she pretends she knows nothing of their attitude toward her outfit. But, she finds herself snapping at any little thing, or acting moody, or withdrawing and acting cold toward all of them. She becomes estranged and continues to react inappropriately for the situation at the time. She experiences a time warp and an alienation because her stifled reactions have come between her and her friends who are unaware that she overheard them. This gap can snowball and widen if something doesn't happen to break its hold on her.

Without some confronting of what's going on for Julie underneath the outward anger and alienation, this estrangement may continue to grow. Over time, friendships can get ruined, feelings can get so hurt that self-doubt and withdrawal can become a way of life. Hopefully, someone will finally get upset enough to try to discover what's wrong. Hopefully, some of their true feelings will be revealed and addressed in a way that the connections remain and relationships continue. Hopefully, lessons are learned and growth occurs. However, too much is left to chance when we don't teach our children how to confront themselves and each other in an honest and fair way. Patterns can develop that negatively affect them for the rest of their lives, and self-images can be crushed or falsely built up in a way that jeopardizes their true sense of who they are and how they should relate to themselves and each other.

- Finally, the third way of reacting, blaming others and projecting our reactions on to others, might play out like this:

Julie would interpret her friends' remarks as a sign of their cattiness and jealousy and either accuse them to their face or within herself. If she speaks, she attacks and accuses them and wants to hear nothing from them except their admission that they are mean spirited and jealous. Unless one of them, Julie or her friends, can break through the reactionary pattern of attack, defend, and counterattack, the outcome will be some form of alienation and anger and hurt. As it plays out over time, there will probably be estrangements, and Julie herself may be isolated from the group or some combination of sub-grouping may form. Unresolved angry and hurt feelings will be circling around under the surface and they may or may not surface from time to time.

In all of these examples, the children involved are at risk unless there is some accountability from one of them. Without good fortune or intervention, the repetition of this pattern with its estrangement and anger and hurt that is left smoldering is a potential hazard for a gradual build up over time of depression, self-doubt, self-loathing, alienation and/or despair. The incidences are small, yet their pervasiveness can wear the spirit down. Left unaddressed, ridicule, sarcasm, or verbal abuse may lead to a form of shunning. Hostility and potential physical violence are always a possible by-product of these out of control unaddressed reactions.

Learning How to Express Strong Emotions Honestly and Fairly

As we have seen, language is very powerful, and learning how to use this power with accountability and fairness does not just happen on its own. We must be taught how to process our feelings, not just react to them. Reactions, our raw data, are essential sources of how we feel about things and the beginning of where to look for what's going on for us. The last thing they should be is the "club" we use to intimidate ourselves or others. Their power lies in their capacity to capture the initial unedited response we have to information. They should help us learn more about ourselves, in terms of how our past has affected us, and in how the present and anticipated future affects us, and in how our convictions influence us. Always, however, they should be dealt with and expressed with accountability and fairness. No matter how strong our reactions are, they should be dealt with respectfully and expressed with strength but not abuse. To give the power of language its rightful place, we must teach the power of articulate speech that captures the intensity of our feelings without using them as weapons. If we have intimacy as our goal instead of winning or punishing, we will use the power of language to inform so that we will be understood and known, not to establish superiority or abuse.

Strong emotions, however, are very powerful forces. As complex paradoxical beings, we have the capacity to experience many emotions, and often contradictory ones at the same time. We can be excited and eager even as we are afraid and cautious. We can feel relieved even as we are worried. And we can feel anger and disappointment even as we feel regret and understanding. The range of emotions we can feel is both a wonderful gift and an awesome responsibility, since every emotion has the potential to free us to be intimate with ourselves or others, even as it has the potential to be used to violate. There is a way to deal with emotions that is honest, fair, respectful and caring, and therefore, liberating and intimate. Yet, there is also a way of using emotions abusively that is violating and oppressive. I would like to discuss with you what we need to know and do if we are to be emotionally liberated, not emotionally oppressed and oppressive.

First, let us explore what it means to deal honestly with our emotions. Honesty requires that we take the time to register and then recognize that we are feeling something, and then seek to discover what it is we are feeling, where it is coming from, and why this feeling or these feelings have been triggered. To be honest we cannot deny, deceive, diminish or exaggerate our feelings. We must claim them and then try to understand them. An honest search of ourselves, of what associations and images come to mind, and what reactions we're having, will allow us to discover as much as we can about what is going on for us. Then, as a journeyer, we must process, not judge, what we discover, trying to understand what it all means and where it's coming from, so that we can be known to ourselves. An honest attitude and an honest approach to ourselves frees us to discover the truth about ourselves to the extent we are capable at the time.

Knowing the truth about how and what we feel and why allows us to know ourselves, and knowing ourselves is what will free us to be true to and intimate with ourselves. It is this integrity, this honesty and this intimacy that frees us to journey through life known to, not alienated from ourselves. Then when we attempt to communicate with others, we are able to begin with an honest claiming of what is going on for us. Any interaction with others that is based on such an honest expression of what we are experiencing has the potential for intimacy and a respectful exchange with another.

It is not as simple as it sounds, however, to be honest about how we feel, and that leads to fairness, the next issue needed for a liberated intimate relationship with ourselves and others. There are many unfair biases that interfere with honesty about how we feel. Sexism and racism are two of the major biases. Sexism unfairly attributes weakness to females and labels emotions that are seen as signs of weakness suitable only for girls and women. It ridicules boys and men if they display any of what is considered the weak female emotions such as fear or anxiety, sadness or upset. Any emotions that are expressed with crying, or gentleness and caring that are expressed tenderly, or feelings of loneliness that indicate dependency and need, are all seen as a sign of weakness. Masculinity is thought to be better served by strength, and anger is seen as a strong emotion. Sexist bias defines masculine as strong, aggressive and independent. The one emotion that boys and men can express to prove their strength and masculinity is anger. Anger is expected to carry a male's emotional life without jeopardizing his image as strong and masculine. Anger, therefore, is over-used by boys and men and under-used by girls and women who are influenced by these sexist assumptions.

The unfairness of considering any emotion as a sign of weakness or strength violates the integrity of the self, which has the need and the capacity to experience every emotion and for whom every emotion is legitimate. To be emotionally honest in the face of sexism is not easy, and it is certainly not easy for adolescents who are in the midst of establishing their sexual identity. In a society where strength is considered superior to weakness, and males superior to females, it is not surprising that adolescent males rely heavily on anger to prove their masculinity and adolescent females who resort to anger to show their strength run the risk of jeopardizing their femininity. To be emotionally honest with vulnerability of any kind is to confront the image of weakness and face it down as a lie. This kind of honesty is not easy; in fact, it is extremely difficult. Yet, this honesty is what is needed.

Anger has its rightful place in our life, but it has no right to dominate it. In fact, any emotion that dominates us, violates us. We should never be dominated by any emotion. As paradoxical beings we must move back and forth between our contradictory feelings and never be overcome by only one. Neither our feelings of vulnerability nor our feelings of strength should dominate us. If they do, we lose our freedom to move and to choose. Feelings of vulnerability must be matched by feelings of strength, and vice versa, or fear and anger will dictate our life choices. If we become only aware of our vulnerability we will be always fearful and afraid to risk. Once this occurs, anxiety accompanies any decision and we become prisoners of our fear. Dominated by the need to feel safe, we lose our ability to venture and our world gradually becomes smaller and smaller and so do we. Eventually we become a caricature of who we are and an exaggeration of what we fear. We lose the integrity of our paradoxical complexity, and as that occurs we lose our freedom. We may even lose our voice, since fear often keeps us silent.

On the other hand, if we choose to deny our vulnerability and only focus on feeling strong, we will become another caricature and an exaggeration of ourself. We will hide our vulnerable feelings beneath the intimidating expressions of anger. If we get upset, we react with anger. If we are disappointed, we get angry. If we are lonely or depressed, we are angry. If we feel hurt or rejected, we lash out with anger. Everywhere and every time our response to an emotional situation is anger. We are loud in anger. It drowns out other feelings and drives them and others away. Dominated by anger, we become alienated from every other feeling hidden underneath it and we prevent both ourselves and others from getting close to us. We become known only from our anger. Because it is loud and aggressive, anger appears to make our world bigger when it dominates our emotions. Actually, it serves only to reduce it and our world is as confined by anger as it is by fear.

Any emotion that becomes our primary and possibly our sole emotional expression, limits our capacity and violates our complexity. Anger, when allowed to get out of control, violates others as well. It has the force to intimidate and the fear it invokes has the added dimension of possible physical violence. Anger, therefore has the potential to be both emotionally and physically abusive and therefore is doubly to be feared.

Yet, these two emotions, fear and anger, keep sexism and racism alive. Whatever racist assumptions are made about any particular race also feed on fear and anger and a false sense of superiority or inferiority. Gender and race are both birth rights, and biased assumptions based on them violate the person with the bias and the person who is the object of it. In racism, the race that conquers and dominates another is considered the superior race, as is the race with the greatest anger. Righteous anger is a racist way of claiming superiority. Often, gentler nations and races are looked down on as too much like women, and female weakness is attributed to them because gentleness is seen as weak.

We are left to deplore sexism and racism and the violation it does to our integrity and our complexity. Honesty and fairness are jeopardized, as we have seen, but so are caring and respect. If emotions are to be treated respectfully and caringly, we must not have disdain for any of them. To be true to our emotions without being abusive with them requires us to treat each and every emotion we have with the greatest care and respect. Just as honesty and fairness go together, so do care and respect. When the gentle tenderness of caring is coupled with the attentive firmness of respect, our paradoxical nature is at one with itself. Respect without caring becomes too stiff and formal, while caring without respect becomes too soft and indulgent. Together, caring and respect bring attentiveness and warmth. Our feelings must be both attentively cared for and respectfully addressed.

What does this actually mean? If we become afraid, we need to put our emotional arm around ourselves and in a caring way, ask ourselves why we feel afraid. If our fear is not honest and fair, it can spin out into hysterical out of control anxiety, and our hold on ourselves must be very firm to exact accountability before we give care and concern. Whatever honest and fair answer we give ourselves after that, we would then need to say how sorry we are that this fear has been triggered and then ask ourselves what we know about why it got triggered and what we need in order to calm it. Then we need to ask if there is anything we want done about it. If the answer is yes, we need to ask what and why. If the answer is no, we need to ask why. In either case, our questions and responses should be non-threatening and invitational even as they are direct and accountable. If what we say is honest and fair, and what we need is respectfully listened to and cared for, we will have responded with the integrity and fairness, care and respect that frees us to be true to our feelings, and not abusive with them.

If we become angry, we would need to firmly put our arm around ourselves so that we can contain the strength of our reaction until we check to see if it is honest and fair. If our anger is honest and fair then we have the space to explore why we are angry and to be respectful and caring of our angry feelings. If our anger is not honest and fair, then we must firmly hold ourselves in check until we discover what emotion is underneath the anger. This is a critical time for any emotion, since indulging an emotion when it is not honest and fair violates our integrity and this throws our system of checks and balances off and it and we become out of control. With anger, that means we may act violently toward ourselves or toward another. Attention to the honesty and fairness of anger is our greatest protection against being abusive with it. Honest, fair anger can be expressed as ours and explored as to why, without lashing out at others and abusing them just because we are angry.

Unfortunately, anger is often used abusively, and we may have learned to react abusively without giving it a second thought. This means we are caught in a pattern that is out of control and therefore we are out of control. Anger is not the only emotion that can lead to being out of control, any emotion can, and the self-indulgence that results from this pattern is destructive. We lose our freedom and our integrity when we are out of control. There is no justification for being out of control even though there may be very understandable reasons for why and how we became so self-indulgent. Our hope lies not in out of control reactions, which only violate and imprison us, but in gaining control of our responses to our reactions, so that we can be free to be true to them, not abused by them.

Expressions of honest, fair anger need to be statements of why we are angry and how it makes us feel. They should not be abusive clubs and dangerous weapons meant to destroy ourselves or another. Destruction and conquest are violent acts and are not respectful or caring to either ourselves or others. They make us into vengeful marauders and self-indulgent bullies who leave devastation in our wake. What we need to be aspiring to is anger that frees us to be true to our strong feelings of unfairness, not anger that violates with its own abusive unfairness. No emotion should be so indulged that it dominates us and spins us out of control.

Every emotion should have its rightful place and its turn, as the occasion arises that calls it forth. And when it takes its turn and we express how we feel, we should be fuller in stature and freer in expression and truer to ourselves than we were before we spoke. If we are an exaggerated caricature of ourselves, out of control and alienated from ourselves, something is terribly wrong. Our liberation is dependent on a complex relationship with ourselves. We must be self-disciplined, even as we are self-indulgent. We must be free to express ourselves even as we are self contained. We must reflect as well as react. We must be honest, fair, respectful and caring with every emotion we feel. We must never endorse abuse and violation either of ourselves or of another.

We must, therefore, learn to process our emotions, not be at their mercy, if we are to be true to them and to ourselves. Understandably, strong feelings need strong language. As a teacher, language is your essential tool. For you to undertake teaching your students how to use language as the powerful tool it is, how to capture their own intensity and their own expression of who they are and what they think and feel, is to really teach the power of language.

The exchange of information should not be geared toward hostility and conquest. Thoughts aren't supposed to conquer feelings, feelings are not the enemies of thoughts. Pretense is not to replace truth even when we don't like it, and discovery is for understanding, not for blame. By using the power of language to inform so that we will be understood and known, rather than to establish superiority or dominance, intimacy becomes the goal of the exchange. Language used for understanding provides the vehicle for preserving the communication system's integrity. Language used for abuse violates the integrity of the system and the person, and not only isn't the point, it should not be allowed.

To give the power of language its rightful place we should teach the power of articulate speech that captures the intensity of our feelings, without using them as weapons, and we should not tolerate the abuse of this power that violates us and our system.

Activities:

The following lists of words used as weapons or as tools are intended to demonstrate this power:

| Using Words as Weapons |

Using Words As Tools |

| to embarrass |

to communicate |

| to humiliate |

to express |

| to put down |

to discover |

| to belittle |

to confront |

| to hurt |

to inform |

| to anger |

to demand |

| to taunt |

to share |

| to defeat |

to join |

| to blame |

to clarify |

| to accuse |

to correct |

| to bully |

to understand |

| to frighten |

to be understood |

| to intimidate |

to illustrate |

| to control |

to separate |

| to force |

to describe |

| to prove |

to orient |

| to trick |

to entertain |

| to entrap |

to engage |

| to mislead |

to lead |

| to lure |

to guide |

| to discourage |

to teach |

| to undermine |

to prove |

| to deceive |

to inspire |

| to lie |

to encourage |

| to manipulate |

to comfort |

| to confuse |

to touch |

| to rile up |

to support |

| to turn against |

to assure |

| to prevent |

to invite |

| to attack |

to protest |

| to counterattack |

to persuade |

| to judge |

to reconcile |

| to imprison |

to protect |

| to wage war |

to liberate |

- Select 15 words from each list of Words as Weapons and Words as Tools, and compose a sentence or two that captures the feeling of the words. In your selection, try to include words and translations that express the attitude that you sometimes or often use to communicate your feelings. In class, take turns reading your sentences to each other with the appropriate tone, and ask classmates what reaction they had, what they felt your intention was, and whether you were using words as a weapon or a tool. Discuss the impact of the sentences and what made some sentences or phrases more powerful than others. What words were harder to convey? Why? What words were easier? Why? What did you discover about how powerfully you are able to use language? How much do you use language as a weapon? As a tool?

- Choose a difficult situation where words as weapons and words as tools are being exchanged that you think you might encounter in a class on the grade level you want to teach. Write the beginning of a script for a role play of it. Leave the teacher's role open. Have classmates play the parts of the students and you play the teacher. Let the role play begin with your script and then see where it ends, depending on how the students' get enacted and how you play the teacher role. Discuss how it went, and why, and what you learned from it. If your class is too large, break up into groups and then report back to the entire class after the exercise.

- Choose an example from your own experience of reactions not being handled fairly, perhaps even abusively, and write a five page paper on what was wrong, what effect it had, and how it could have been dealt with differently and fairly. Discuss how you learned to handle your reactions and what will be hard and what will be easy for you when you teach self-expression with accountability. Take a position on how you think the outcome would have been if there had been fairness, integrity and accountability.

- Write a paper on how your gender and your family have shaped your relationship with anger and fear. Explore your own biases relative to gender appropriate behavior part in this relationship, regarding anger and fear. Discuss the role nationality and race have played and the impact they have had on you, also. Take a position on how you want to express anger and fear.

- Present a paper for class discussion on how processing allows us to treat information respectfully and fairly, how analyzing information shortchanges feelings and sets up a hierarchy of doing and solving, and how judging and blaming are psychologically abusive.

|